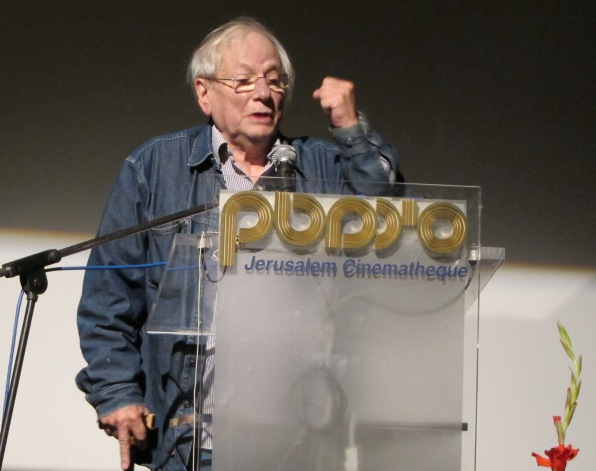

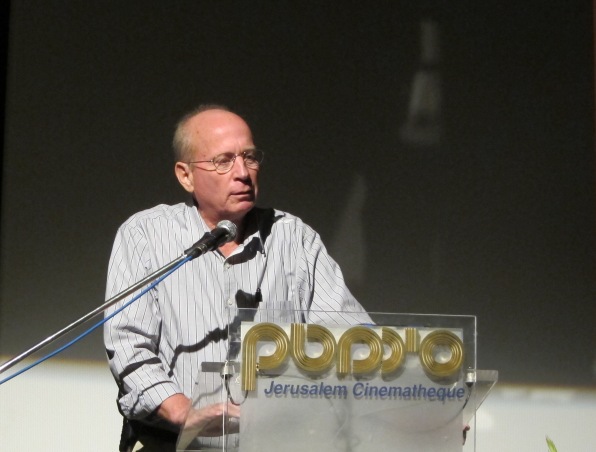

Who are our heroes? How and why has our definition of a hero changed over time? What is the connection between an actor and the character she or he portrays? What are the underlying values revealed by these choices? These are some of the questions raised by filmmaker Renen Schorr, Director of the Sam Spiegel Film & Television School Jerusalem, as he opened the 2011 conference on The Cinematic Hero. Now in its third year, the conference with its roster of film industry members, academics, musicians, activists, writers and others, may be seen as a barometer of the Israeli cultural climate, reflecting concerns current and timeless through the filter of cinema.

The festive opening of the Sam Spiegel School academic year, the conference is a training ground for the students who produce the event, a lively initiation for new students and a reminder to all of the power inherent in film. The marathon 40 speaker event is open to the general public free of charge, with the individual talks made available on YouTube. When Schorr urged, “We must demand of ourselves to search for new Israeli heroes on the screen,” his words resonated with the intention to influence and inspire not only the emerging generation of Israeli filmmakers, but the wider span of Israeli culture.

“My name is Shoshana Dreyfus, and this is the face of Jewish vengeance,” said investigative journalist and attorney Ilana Dayan, host of Uvda (Fact) on Channel 2, quoting from the clip of Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (2009) that had just been screened. Dayan explained that her choice was not influenced by the film or the director, but by the heroine’s strong need to tell her story. By the time the words are spoken in the film, Shoshana (Melanie Laurent) is no longer alive and the screen from which her words emanate is already in flames. Telling the story is so important to Shoshana that it is worth dying for, “that is where I felt a connection – to that need to tell the story,” said Dayan, “and perhaps, also to the ease with which a story can be distorted.” Asking the audience to set thoughts of the film aside for a moment, she asked, “Why is it so important to tell the story? To ask, to investigate, to know, to keep the channels of communication open, from blogs to the main news broadcast. The answer is clear to me: as a society we must hear in order to know, to understand and to choose. I feel an affinity to those who feel the need to tell the story…one day we’ll wake up and realize there is no one left to tell the story, to tell the truth without fear or bias.”

“I love the anarchism, hating the establishment, criticizing the canon, making a commotion, standing alone against the world, against all odds,” Shaanan Streett brought the groove with a rap on The Blues Brothers (John Belushi and Dan Akroyd as Jake and Elwood, in the 1980 John Landis film) that no translation can touch. Reader – you’ll just have to wish you were there. Streett, lead singer of hip-hop/funk socially aware band Hadag Nahash and founder of the Festival for a Shekel (a music festival that takes place in a different city each year, with the admission price an egalitarian 1 NIS), said that the first time he saw the movie was on the Israeli Broadcasting Authority Channel 1, with the line “We’re on a mission from God” deleted. Of Jake and Elwood, Streett said, “They have bad taste in food, their clothes look like Hassidic diamond dealers, but they have great taste in music – Cab Calloway, Ray Charles, James Brown, Aretha Franklin…and they believe that through music, you can change the world.”

One way to change the world is through education, and lawyer/activist/writer Yuval Elbashan, founder of Yedid, The Association for Community Empowerment, chose to look at the character of Daniel Lefebvre (Philippe Torreton) in Bertrand Tavernier’s Ça commence aujourd’hui (1998). The film’s title – It all starts today – refers to the student protests of May 1968, and the call to action expressed in this and other graffiti slogans that covered the walls of the Latin Quarter in Paris. Lefebvre is the Director of a preschool in a poor mining village in northern France, “Immersed in ideals,” said Elbashan, “he wants to change the world, working within the system, yet he is subversive as well.” As he works in the community, Elbashan said that Lefebvre “begins to understand the complexity of life, that there is no one truth, but several versions of it…how hard it is to effect this tikkun (change, healing).” Elbashan chose Lefebvre as his hero because although he fails, and breaks down, Lefebvre returns to work in the school, quoting Lefebvre’s girlfriend in the movie: “You can’t always help people, but you can love them.”

Nahman Ingber, film critic, teacher, researcher, and recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2011 Jerusalem Film Festival, spoke of the changing image of the hero, from the powerful hero in folk traditions of storytelling, when heroes were almost exclusively male, to a different cultural consciousness, that of the anti-hero, the one who is acted upon by forces greater than himself, “He cannot act, he can only talk and talk, and wait, like Vladimir and Estragon.” Looking at the character of Lidia in Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte (1961) Ingber said, “In the early 60s, Antonioni brings this alienation, sense of detachment, and lack of connection to cinema, the foundation of modern cinema.” The male hero of action is replaced by a female figure, said Ingber, “Lidia, the wife of the writer, understands that there is no longer any meaning to existence, love, or relationships. Her face expresses all that her consciousness perceives. The landscape and urban architecture of Milan reflects the soul’s internal contradictions. When she encounters action – it is male, violent, and meaningless.”

Questions of action and heroism figure prominently in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Filmmaker Judd Neeman looked at the character of Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart), the “City slicker” represents the law and its values, while John Wayne represents the other half of the myth: the winner is the one who has what it takes to survive, as Neeman said, “It’s the gun belt, the fastest draw that determines the outcome.” Taking place in a territory that is in the process of becoming a state, the gun and the book of law, embodied by Wayne and Stewart, vie for the role of hero. Neeman said, “Without law and order there can be no state and no culture.” He spoke of the United States as a nation that is not a “blood relations,” (a nation of homogenous ethnic origin) but is a nation founded on a “book of laws.” Referring to Israel, he said, “We claim to be a nation of blood relations, but actually, we’re a bunch of immigrants and without a book of laws we will not survive.”

Keshet Broadcasting CEO Avi Nir spoke of the nameless hero, juror #8 (Henry Fonda), in Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men (1957). Although the situation in the film is similar to the structure of Westerns – one against many, Nir said of the character, “He is a cinematic hero without action or movement, who does not care about winning…he just wants to have his say, although he is not certain that he is right. If there is something that caught my eye, it is his skepticism…a hero is usually led by his ego and the motivation to win. He (juror #8/Fonda) only wants justice to be done.” Nir further commended Lumet and Fonda for taking what was originally broadcast as a black and white television movie to the cinemas during the heyday of color, resulting in an Oscar nomination and a box office disaster.

A different perspective to the discussion was introduced by Oded Kotler, actor, director and recently appointed Director of the Herzliya Ensemble: that of the actor in relation to the role. Kotler showed a gripping scene from Elia Kazan’s East of Eden (1955), in which Cal (James Dean) presents his father with a unique birthday gift, which is cruelly rejected. Cal’s response is heart-rending and visceral, watching the scene I cringed in my seat. Kotler reminded the audience that an actor is not someone who merely “performs what others have instructed him to perform,” but rather takes the material “deeply into his inner self, his being…acting requires endless searching and researching.” In terms of the specific scene, Kotler revealed that Dean’s stage instructions were to walk out of the room when his gift is rejected. Yet during filming, Cal remained fixed on the spot, broken, bent over, almost collapsing, then threw his arms around his father saying “I hate you.” Kotler commended both Dean’s creativity and Kazan as a director who ultimately decided to allow this improvisation to become part of the film.

Threads of narrative wove their way through the morning sessions, creating connections between people and issues in film and in life. Speaking of the way we seek out different heros during the different stages of our lives, Ari Folman invoked his childhood hero, Zvika Greengold, another speaker at the conference. Greengold was awarded the Medal of Valor for his actions in the Yom Kippur War as an IDF tank commander of ‘Koah Zvika’ (further intertextuality – the story of Zvika’s courageous fight was told by then-military correspondent for BaMahane (the IDF magazine) Renen Schorr).

The changing image of the hero was further discussed by filmmaker Avi Nesher, who looked at Sam Pekinpah’s Pat Garret and Billy the Kid (1973) as he reflected on his own current project, adapting Yoram Kaniuk’s memoir 1948. “Film does not like ambivalence; it wants to present reality as something whole and with a unified meaning. The heroes of 1948 – how does one present them?” As a child Nesher said he felt that they were like the cowboys in Westerns, Nesher said, “They were honest people who never drew first, shooting only when others shot at them…it took some time for me to realize that life doesn’t work that way.” Nesher described Pekinpah’s film not only as a negation of heroes, but a negation of the desire for heroes. A cautionary tale whose message is: beware of storytellers. With musicians Bob Dylan and Kris Kristofferson cast in leading roles, Nesher said that in this way Pekinpah works against the ability of cinema to instill belief, “you never forget that Bob Dylan is Bob Dylan. There is no redemption, [Pekinpah says] I’m not selling illusions, I’m selling fabrications…I find that liberating.”

Author Yoram Kaniuk was suave and charming as the hero he chose, Fred Astaire, regaling the audience with his memories of crashing a wedding in Hollywood and literally standing in his hero’s shoes – dancing with Ginger Rogers. Calling Astaire the “greatest dancer I have ever seen,” Kaniuk quipped, “I recently read that his grandfather was Jewish, that really moved me.” Reflecting on his recent legal victory to be referred to as “without religion” on all official documents, Kaniuk went on to say, “I am no longer Jewish.” Listening to Kaniuk describe his cinematic hero – “he was always himself, he was never kitsch, he didn’t try to make anyone love him” – one might be tempted to see an affinity between Kaniuk and his view of Astaire.

Attending two out of six sessions provided this writer with a very partial yet stimulating view of the conference, with much material for further reflection as Zvika Greengold, took the mic, and said, “I am not part of the film industry and haven’t seen as many films, I feel part of the Jewish destiny, by the way, I am Jewish.” Currently Mayor of Ofakim, a development town in the south of Israel (reminiscent of the town described in Avi Nesher’s Turn Left at the End of the World), Greengold showed a scene from Otto Preminger’s Exodus (1960) featuring Paul Newman as Ari Ben Canaan. Greengold said, “I was born in Kibbutz Lohamei Haghetaot (Ghetto Fighters) in 1952. My mother came to this country as an immigrant, she didn’t even have a suitcase. It took me many years to realize that our collective parents, the refugees, were heroes. We (my generation) saw the Palmach as heroes. I identify with the difficulty of being a soldier in wartime. War is often glorified; the film industry has contributed to that image. War is hard, it’s abhorrent, and we need to do everything in our power so that there will be no more wars.”