The law – both in promulgation and execution – is a thankfully abstract concept for most people. We know that it is there, we recognize its utility as a tool for maintaining order in society and protecting us from the excesses of others. But in the same vein, we are not necessarily conversant with the principles upon which it operates. Perhaps we need not be burdened with this technical information; perhaps it is enough to share the presumption of faith in its ultimate intent, of ensuring fairness and evenhandedness: not only will justice be done, but that it will be seen to be done.

The anomalous situation in the Occupied Territories – under Israeli control but not subject to Israeli law – is the subject matter of The Law in These Parts, an intelligent, provocative, and thought-provoking documentary by Ra’anan Alexandrowicz and Liran Atzmor. Most Israelis are aware of the fact that Israeli law does not apply in the territories occupied by Israeli forces after the 6 Day War, but rather military law. But what is this law? To whom does it apply? How is it applied? And, most importantly, does it respect the Rule of Law, the fundamental principles of justice and evenhandedness that underpin its authority?

“The expression the Rule of Law,” remarks former Justice of the Supreme Court of Israel Meir Shamgar in the epigraph to the documentary, “refers not only to the vigilant enforcement of the defined norms of a given legal system: It comprises the even more important component of respect for the law, and to the confidence and reliance of every individual that justice will be done.” The law derives its validity – even in cases such as this, when applied to an unwilling population – from the presumption that it is manifest, accessible and transparent.

The concept of a separate legal system in the Territories is the source for any number of conceptual arguments, not all of these necessarily enlightening. To its immense credit, what The Law In These Parts does is to sidestep – up to a point – the polemics, and begin instead with first principles: exploring the history and execution of military law in the territories. The value added content is that this is done with the explicit co-operation of those tasked to enforce it, former administrators – judges, prosecutors – of Military Law in the Territories.

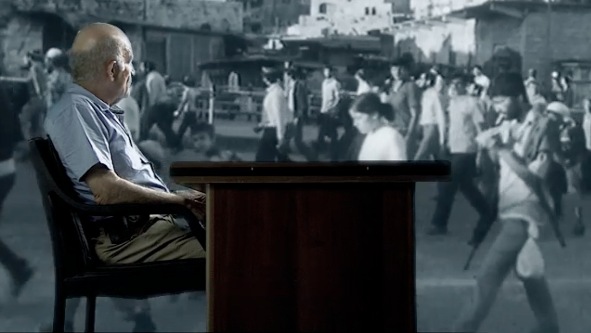

An aesthetic charge lingers through the bulk of the documentary, which largely consists of former military prosecutors and judges exploring, explaining, and to some degree justifying the operation of Military Law. Archival footage runs in the background, a reminder that the matter under discussion is not hypothetical, but rather something with an important human component, and human consequences. At a point, I find myself wondering whilst staring at grainy black and white footage from another age: Who are these people? What did they think of the situation then? What would they think of it now, should they still be alive? It introduces a powerful human component into what could easily descend into hypothetical considerations. Palestinians citizens and Israeli soldiers, both are touched – both are affected – by the preservation of the rule of law. Or not.

Why military law, the documentarian asks. To prevent chaos, the absence of order, is the response. “(It is) the machinery to ensure that life will continue, would not come to a halt.” Which makes perfect sense, until one considers the next point – if so concerned, then why not Israeli law, already established and with a functional, independent framework? The interviewee, a former military judge, grimaces a little uncomfortably. “To do so may imply certain things you may not want. Annexation, citizenship…”

Ra’anan Alexandrowicz – whose other films include 2003’s James’ Journey to Jerusalem – is an intelligent filmmaker. He is also a playfully provocative one. In one voiceover, he reflects: “In films like this…the viewer judges reality as it is presented.” Presented by who? Alexandrowicz does not shy away from the fact that “reality,” as presented in his documentary is shaped by personal prejudices. This is a welcome honesty in an age where journalism strains after an unattainable objectivity. When an interviewee acknowledges that he would accept the word of the Shabak over that of a detainee, his voice over cuts across the interview. The filmmaker, like the military judge, will only acknowledge that which he wishes to acknowledge. He will not allow for the documentation of information that weakens his central thesis, such as the judge’s dedication to duty. But of course, thus operates the legal system in the Territories too. Unfairness begets unfairness, and Alexandrowicz introduces this in novel fashion.

The philosophical thread that runs through The Law In These Parts is discomfiting: even if the principle of Military Law in the Occupied Territories could be absolutely justified, its execution – in this case – cannot. Examples of the latter are numerous unfortunately: Administrative detentions, punitive house demolitions, targeted assassinations – extra-judicial executions by any other name. Alexandrowicz coaxes startling statements from his interviewees – whom, one must remember, were all part of the legal administration of justice in the Territories. That security concerns must trump human rights issues, for instance. That justice must sometimes be subservient to order. That – implicitly – the concept of the Rule of Law is relative, rather than absolute.

The sharpest – and most enlightening – exchanges in the documentary are those between the documentarian and Meir Shamgar, Military Advocate-General between 1961 and 1968, and President of the Supreme Court until 1995. Now in his late 80s, the distinguished jurist is attentive, courteous and razor sharp; he believes unwaveringly in the primacy of the rule of law, and of the role that the Supreme Court has played in maintaining this.

But has the Supreme Court actually done this? One wonders. Take this anecdote, for example. In 1980, the Supreme Court stopped Ariel Sharon – then Minister of Agriculture – from seizing private Palestinian land, ostensibly for security considerations but in fact as a means to establishing new settlements. The court ruled that this was impermissible; Sharon immediately convened a meeting of his legal experts to explore gaps in the judgement. One participant recalled an antique ordinance from the Ottoman Empire, the Mawat (Dead) Law. In essence, land that fell outside the precincts of an established village – beyond the sound of a rooster crowing, in its romantic formulation – and remained uncultivated for 3 years reverted to the ownership of the Empire. Or its successor, in this case, the Military Administrator of the West Bank.

“Be in my office at 8 tomorrow, with or without your rooster,” Sharon ordered. And thus, a means of circumventing law was found. If the letter of the law is preserved, but not the spirit, it is hard to determine that the rule of law did prevail.

Alexandrowicz’s thesis, ultimately, is a subversive one; that the ostensible enforcement of the rule of law in the Territories has perpetuated an unsatisfactory situation, by giving a veneer of legality to an ultimately untenable exercise, the occupation that has now persisted for 43 years. When he puts this to Shamgar, the latter explodes indignantly. Would it be preferable for there to be no rule of law, rather than one that produces unanticipated consequences? This was the conclusion of a research project by a professor at the Hebrew University, the documentarian observes. “Anyone can become a Professor at the University these days, it seems,” Shamgar interjects, dismissively.

One sees his point. The rule of law ought not be circumvented on the basis of the potential for unforeseen – unforeseeable – consequences. But then, the rule of law should not be undermined ab initio, either; and Alexandrowicz makes a powerful case for this argument, that true justice has never been available to the Palestinian residents of the West Bank and (until 2005) of Gaza.

Documentarians should never be presumed to inhabit the higher ground as of right, and it must be noted that Alexandrowicz asks the questions rather than proffering solutions. It must also be said that the line between necessary security precautions and important legal concerns can be extraordinarily thin. But still, one returns to Shamgar’s words at the beginning of the film: “The expression Rule of Law…comprises the more important component of respect for the law and the confidence and reliance of every individual that justice will be done.” The emphasis is mine: it ought to be yours too.

The Law in These Parts will be screened at DocAviv Galil 2011 on Wednesday, November 30 at 18:00 at the Performing Arts Center in Maalot-Tarshiha. The film premiered at the Jerusalem Film Festival 2011, where it was awarded the prize for Best Documentary. Additional screenings will take place: November 28th – Jerusalem Cinematheque, from December 1 – Herzliya Cinematheque, December 12 – Sderot Cinematheque, December 14 – Tel Aviv Cinematheque. Full details are available on the film’s website in English, www.thelawfilm.com/eng.

Comments are closed.