There’s much to for the cultural epicure to savor at the EPOS International Art Film Festival, the tempting feast includes features and documentaries on art, theatre, dance, literature, music and film. For this writer the pleasure begins in reading the program, preferable equipped with a highlighter (usually four) to mark all the films I would like to see. After several hours, contemplating the intricate four color design, I concede and narrow down the list. By that time, the film titles are a blur and the process of choosing which film to see begins to feel almost random.

Inevitably, this random juxtaposition of films in a festival creates connections; moving from one film to the next, associations arise, a theme begins to play in the mind.

I began with Ai Weiwei – Without Fear or Favour, directed and produced by Matthew Springford. A contemporary Chinese multi-disciplinary artist who has orchestrated vast projects such as Sunflower Seeds at the Tate Modern (currently on view at the Mary Boone Gallery in New York through Feb 4 ), widely known beyond artistic circles for his part in designing the Beijing “Bird’s Nest” Stadium for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, Ai Weiwei made international headlines last spring when he was arrested by the Chinese authorities. Part of a BBC series edited and presented by Alan Yentob, the film was first broadcast before Ai Weiwei’s arrest, and provides a fascinating look into the life and work of the artist.

Politics have played a central role in Ai Weiwei’s development from the start, yet the impact and resulting choices made by the artist are not always obvious and certainly not simple. Growing up as the son of a poet punished and exiled to the edge of the desert by the Communist regime, Ai Weiwei’s childhood was marked by an enforced self-sufficiency and inventiveness. In the absence of all infra-structure and support, those in exile had to create a life out of the meager supplies available in nature, even building their own homes by making clay bricks, as Ai Weiwei says in the film, “You start to learn everything from a very early age.”

The life Ai Weiwei has created involves many journeys, including a decade spent in the New York art scene. Today he lives and works in China; his art reflects a deep engagement with the culture and current socio-political environment, a connection as strong as it is painful and complex. Following his release in June 2011, he is barred from leaving the country.Yet even as he in some sense cut off from the world (he remains under surveillance and at times has had his twitter account shut down), Ai Weiwei and the porcelain sunflowers have become a symbol of artistic freedom and courage, a message of hope to millions.

The power of images and the relationship between politics and art is played out in a very different vein in Bollywood – The Greatest Love Story Ever Told, written by Sabrina Dhawan and Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra and directed by Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra and Jeff Zimbalist. A brilliantly directed and edited film, it radically departs from the didactic style of documentaries to work through image, sound and pacing to convey the emotional impact of Bollywood. Scenes from Bollywood movies are interspersed with archival footage from India’s political history, connecting art and politics through association without imposing a particular narrative or interpretation, leaving the individual viewer to consider the implications. Interviews with prominent actors and directors as well as people on the street add to this sensual, seductive portrait of the tantalizing Bollywood film industry. The potential of film as a manipulative medium is undeniable, demonstrated here by masters of the art: watching the film I was conscious of being thoroughly manipulated and I loved every minute of it.

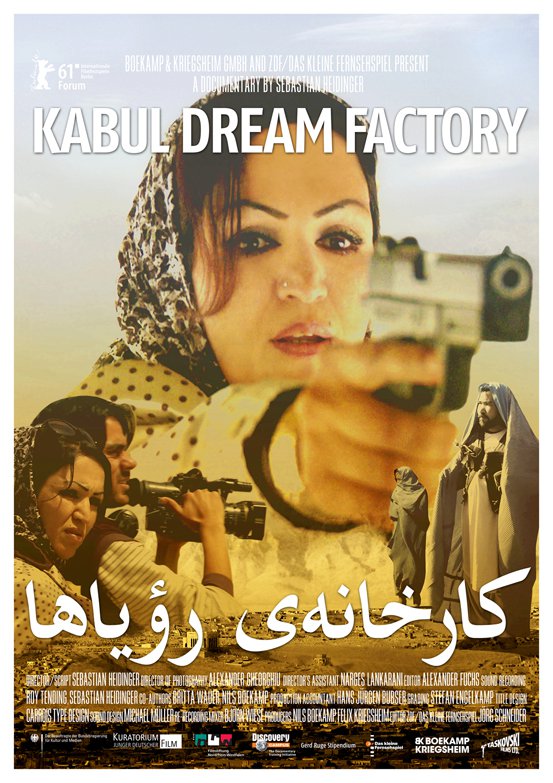

Kabul Dream Factory depicts a dramatically different film industry, political reality and approach to documentary. Director Sebastian Heidinger takes a ‘fly on the wall’ approach, following Saba Sahar, a policewoman turned filmmaker in Afghanistan. Clearly made on a very low budget, and filmed under extremely difficult conditions, there is much that remains opaque. Sahar is a rather mysterious figure, she is clearly a strong, resilient woman, yet we do not learn much about how she came to be “Afghanistan’s first woman film director.” Reluctant to discuss her personal life – when asked in an interview how she feels about her marriage at age 17, she rejects the question as being inappropriate, irrelevant to a documentary film. Yet as she goes about her daily routine, tireless in her attempts to create films that empower women (clips showing Sahar starring as the bad-guy bashing heroine Setara add verve and fun, very basic in their filmmaking technique, they also appeal to very essential fantasies) and travelling throughout the country with a mobile cinema to make sure that the films reach their audiences, her courage and persistence are quite moving.

The strength of Dave Brubeck – In His Own Sweet Way is aptly expressed by the film’s title: the film reveals and revels in the music and the man, a pleasure and inspiration. The film is a tribute of one artist to another; Clint Eastwood initiated this project after hearing Brubeck’s Cannery Row Suite in 2006. Directed by Bruce Ricker, this film makes the excellent choice of allowing Brubeck to tell his own tale, in words and music, with music happily dominating. One not only understands, but experience’s Brubeck’s contribution to jazz. It is a heady, delightful experience.

The film also revives a somewhat forgotten chapter of cultural diplomacy: Brubeck, along with Louis Armstrong, Dizzie Gillespie, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington and others, were cultural ambassadors, travelling to different countries to share American music and culture during the Cold War. Listening to the influence of these travels in Brubeck’s music, reveals the ways in which these encounters develop in new and unexpected directions. On a mission to spread American cultures and values, these musicians were also opening up to the world, musically, culturally and politically: a mutual learning experience sowing the seeds for world music and cultural dialogue. As Brubeck says in an interview with Walter Cronkite after his tour: “Maybe the thing that binds humanity together is the heartbeat. Rhythm is an international language, not harmony or melody.”

EPOS, the International Art Film Festival, will take place from February 1 – 4, 2012 at the Tel Aviv Museum. The full program may be found on the festival website.