At first blush, Hanoch Levin and Alan Bennett could hardly be considered similar playwrights. The first was fond of the dramatic overstatement, and diced with censure and censorship for much of his career. Bennett, on the other hand, has over 40 or so years of productivity has settled into the most comfortable of British institutions, that of an (unofficial) national treasure. Levin’s plays are acerbic, cutting; Bennett’s, gentle and understated. But, as two documentaries screening at EPOS – The International Art Festival – suggest, the two might not be as far apart as first impressions suggest. Both use their work – albeit in very different ways – as vehicles for social satire; the plays of both are imbued with the passion of a well travelled emotional hinterland.

Written and directed by Nitza Gonen, The Child Doesn’t Dream Any More takes the direct route to analyzing Levin’s work. Following cast and crew as they prepare to premiere an operatic adaptation of Levin’s play The Child Dreams, the documentary traces a collective journey of discovery, as they strive for the underlying meaning of the original work.

The Child Dreams – one of the many plays that Levin wrote in a prolific career cut short by cancer at the age of 55 in 1989 – is a powerful allegorical work, taking as its starting point the doomed journey of the MS St.Louis. The boat was a German liner that searched vainly for refuge for its 900 Jewish passengers in 1939, before returning them to Germany and certain doom. The dramatic flourishes of the original play lend themselves well to an operatic setting; even so, the production team – including composer Gil Shohat, and the Austrian artist Gottfried Helnwein, responsible for the haunting, at times viscerally disturbing stage settings and costumes – shy away from leaping to obvious.

We get the sense that the key to the play lies within the central character, the Child. Brutalized and traumatized, his father is murdered and his mother sacrifices herself for his salvation. But these sacrifices all come to naught; one wonders whether Levin – consciously or not – was drawing on his own experiences of a difficult childhood. Levin, notoriously, gave very few interviews in his lifetime; everything he had to say he said in his plays, he once remarked. But what can one take from his play – and the opera – and how far is it leavened by the transmutation of personal experience? The last word lies with director Omri Nitzan: “The Child reveals the world,” he observes. “It’s typical (of) Levin that he reveals what we don’t see, what we are blind to.”

Much like the playwright himself, Alan Bennett and the Habit of Art is digressive and entertaining, a little undisciplined and not at all adverse to slipping in the occasional surprise, almost as if to make sure that the audience are actually paying attention.

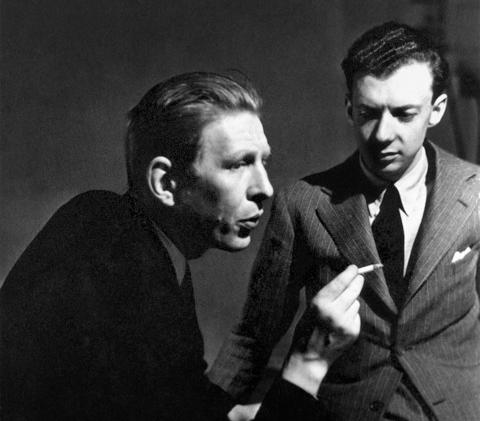

The Art of Habit, produced at the National Theatre in London in 2010, imagines a final meeting between the poet W.H. Auden and the composer Benjamin Britten. Once close friends and collaborators, they fell out with one another and spent the last quarter century of their life avoiding one another. Bennett – author of The Madness of King George and The History Boys, amongst other plays – talks about the process of writing the play in his self effacing manner. Nicholas Hynter, artistic director of the National and Bennett’s long term collaborator, fusses over Bennett proprietorially, nudging the play in the right direction. “You come to the point where one needs encouragement,” Bennett says by way of explanation.

Hynter has an interesting thesis about what the play is really about; A/B, its working title, referred to the initials of the two principals. “They’re Bennett’s initials too,” he points out, a morsel that the documentary leaves hanging, tantalizingly, for a while.

Auden and Britten, close friends but polar opposites temperamentally, were both gay at a time when it was a criminal offense in the United Kingdom. But whilst Auden was open almost to the point of uninhibitedness about his sexuality, Britten was much more circumspect. There is no suggestion that they were lovers, but it adds to the tension of their friendship and fictitious reunion.

The breakthrough that pushes Bennett’s writing of play along is a curious framing device: He relates the story through the filter of a theatre company rehearsing a play about a fictitious meeting between Auden and Britten. It allows for a suitable distance from proceedings; it also proves a useful foil, as it allows Bennett the opportunity to explore his principals without being forced to pass judgement on them.

Or is it just his characters? Bennett, quite reasonably, has never sought to live his private life in the public eye. A diagnosis of cancer, with a “less than 50%” chance of survival, went unreported until several years after it went into remission, for instance. Likewise, Bennett has never hidden his sexuality, but has never made it a part of his identity. Hynter – again – makes an astute observation about Auden, Britten and Bennett. Might the characters resemble conflicting impulses within Bennett, and might writing about them serve as some form of catharsis?

One can never know with these things, of course. And perhaps one needn’t. Neither documentary seeks to make the decisive statement; as is best with things like this, they both treat the subjects of their hypotheses – however obliquely couched – with the detached dignity that they deserve.

For additional information on screening times and the full program, consult the EPOS site.