Ghetto, a play by Joshua Sobol describing daily life in the Vilna Ghetto and the theatre company created there under impossible conditions, will premiere at the Cameri Theatre on March 8, directed by Omri Nitzan. For Noam Semel, Director of the Cameri, the play has come full circle – it was first produced at the Haifa Theatre in 1984, when Semel was its director.

Omri Nitzan recalled sitting in the Haifa theatre offices one evening with Semel, when Joshua Sobol came to tell them about the diary written by Herman Kruk, describing life in the ghetto. Says Nitzan,“It was a source of inspiration for Joshua. Now, Noam Semel lives twice – he is always doing several things at a time. While Joshua was telling us this touching story, Noam was moving non-stop at his desk, opening drawers, picking up pens…I told Noam – he’s talking about something very precious and important to him. Then Noam picked up the papers he’d been fiddling with, and held them out for Joshua to sign – it was the contract for Ghetto.

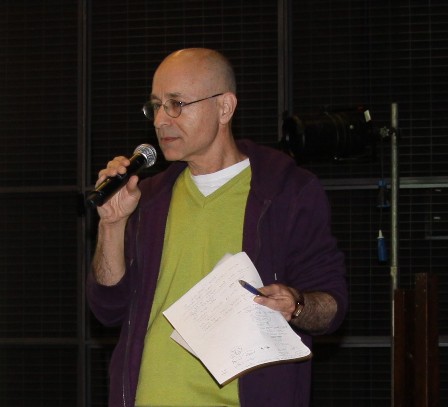

Playwright Joshua Sobol said, “My inspiration for writing the play was my discovery of songs written in the ghetto. In a book about the partisans of Ghetto Vilna I found the comment: “The underground objected to the theatre in the ghetto.” It was the first time I realized that there had been a theatre in the ghetto. I started to research the topic, it was then 1982 and many of the people involved were still alive. Irena Lusky wrote a book about her experiences which shatters many myths. It was written from the perspective of a girl of 16, about first love, sex, without any inhibitions. When I spoke with her she asked me, “Why don’t you talk to the Theatre Director Israel Segal?” It turned out that he was living at the time on Gordon Street in Tel Aviv. I met with him. When I asked him how he found costumes for the theatre, he said, “We didn’t lack for costumes. There were many clothes from Ponar [the death pits].”

“They performed satiric sketches, cabaret – there are no remaining texts from these. Some are humorous; sometimes the humor is a kind of black humor, sometimes romantic songs. Lusky wrote in her memoir that after a hard day’s work people would come home, shower, and go to the theatre. I visited the YIVO archives in New York. They had documents of ticket sales. The theater had 315 seats and they usually sold 330 – 350 tickets each evening.”

“From my perspective,” Sobol concluded, “this is not a play about the Holocaust, but about the Jewish world that disappeared. In the 1920s the Vilner Troupe performed O’Neill, Strindberg, Pirandello, The Dybbuk – it was a modern and even avant-garde theatre. They were a testimony to the spiritual force of European Jewry.”

Stage designer Roni Toran explained that the conversation with Segal (played by Gadi Yagil) provides the framework for the play –life in the Vilna ghetto is presented through Segal’s memories. “Working with the freedom of memory,” said Toran, “we placed emphasis on the dramatic situation rather than historical accuracy. There will be a transparent screen, on which an image of a Tel Aviv street will be projected, and behind you can see the set – the ghetto slowly emerges from Israel’s memories.” The chaos and crowded conditions of the ghetto will be expressed in the three huge piles of clothing, furniture and books on the stage, each of which will also contain hidden exits for the actors. Toran further said, “This is a group of people who are locked in the closed space of the ghetto. They have been cast here like the piles of clothes and books.” His inspiration for expressing that sense of imprisonment came in part from the works of Mona Hatoum, a Palestinian artist born in Beirut and living in London, whose grid-like work Current Disturbance (1996) is at the Israel Museum (due to the extensive renovation project, this wing is currently closed). Hatoum’s work is minimalist in form, personal and political at once, a grid with no entrance or exit, recalling a prison cell. The grid contains many light bulbs that flicker on and off, at different levels of intensity – an effect evoking associations of searchlights and electric fences, but also perhaps, beacons of hope.

The play expresses the dissonance between the life created in the theatre – joy, laughter, song and dance, as well as the sense of togetherness, and the experience of being crowded into the ghetto, in unbearable living conditions, dependent on the whims of the Nazis, under the constant threat of death. While the play itself is fictional, it is based on historical figures and events.

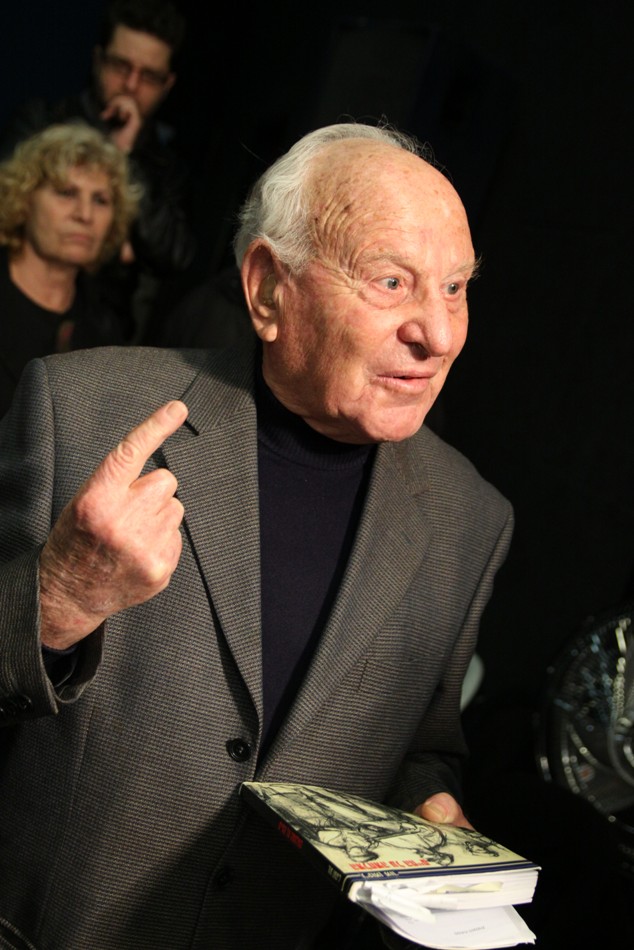

After the presentation, a man who had lived in the Vilna ghetto, Yom Tov Litman (as he said – the name by which he is called to the Torah), recalled his experiences there. “I visited the theatre; I couldn’t come to all the plays because I didn’t have enough money.” Litman recalled the Nazi Kitel, saying, “What I saw now in the play was true, Kitel would come to the ghetto and play with the orchestra. Not in front of an audience.” Litman also spoke of the conflicts between the different factions in the ghetto that are brought to life in the play Ghetto. He worked on behalf of the underground in the Judenrat – specializing in assigning people to apartments, dividing up the living space – 2 meters per person. “If the apartment was 40 meters I was an expert at knowing how many people I could fit in there.” Speaking of ghetto commandant Jacob Gens, Litman said, “He could have saved himself but due to his sense of public duty thought that he could save those who would be the most essential, and he made the selection. He didn’t cheat or take bribes. Historically, he betrayed his people…Life in the ghetto, every hour is borrowed. The uncertainty: what will happen tomorrow? That was our constant fear.”

Scenes from an open rehearsal of Ghetto, photographed by Elizur Reuveni:

The songs used in the play are authentic songs written in the Vilna Ghetto between the years 41 – 44. Kruk’s diary, The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania, was published in 2002 by Yale University Press.

Ghetto by Joshua Sobol, directed by Omri Nitzan

Cameri Theatre, 19 Shaul HaMelech Street, Tel Aviv

Performances beginning March 8, performance with English subtitles on April 10.

Tickets: www.cameri.co.il, 03-6060960

Photos from the premiere can be seen on Midnight East’s flickr page.

AYELET DEKEL