Working with a weak text doesn’t give a director much to go on, however, working with an iconic text presents just as much of a challenge, especially if the play in question was written by Hanoch Levin. Levin (and other legendary directors, such as Michael Alfreds who directed Suitcase Packers at the Cameri in 1983) directed many of his own plays, imbuing those productions with the aura of the original definitive version. Any given Israeli audience of a contemporary production of Levin’s plays is likely to include people who saw the “original,” and perhaps even a few members of the original cast, enough to induce a certain anxiety in even the most intrepid director.

Udi Ben Moshe enters this arena boldly. Ben Moshe has a full-bodied, buoyant, musical style which serves the Cameri Theatre’s new production of Levin’s Suitcase Packers brilliantly, bringing the text to life with energy and emotional impact. Levin’s texts are deceptively simple, densely textured with word play and poetic allusion, a stark appraisal of the human condition, deriving much of their humor from human misery.

Ben Moshe has fun on this existential playground with a set designed by Ruth Dar and lighting design by Avi Yona Bueno (Bambi). Placing the characters almost literally in the void, some of the action takes place on a completely empty set, the actors illuminated against endless black space. At other moments a theatre of shadows appears in counterpoint to the action in the foreground, moving behind an illuminated scrim. The play opens with lively music, composed by Keren Peles, accompanying the actors as they step out, suitcase in hand to line up across the front of the stage. There they stand, silent, grimly staring out at the audience. This vignette frames the play, a wordless understanding between the actors and audience; we all know that they are going nowhere.

There is a repetitive structure to the play that underscores the repeated cycle of human life. Birth, marriage, new birth and death, that is the best case scenario; for some there is nothing between birth and death but a long stretch of loneliness and longing. Sounds monotonous, but all that misery is peopled with vibrantly colorful characters. Set in an unspecified present time, the play revolves around several families living in the same neighborhood: the Schusters (Ezra Dagan, Rosina Cambos, Tamar Keenan, Odelia More-Matalon), the Gelernters (Rivka Michaeli, Dror Keren, Avi Termin), the Glubchiks (Ohad Shachar, Gilat Ankori, Avi Graynik, Hanna Maron), the Hofshtaters (Ezra Dagan, Esti Kosovitzki, Udi Rothschild), the Zehoris (Yoav Levi, Andreea Schvartz, Shlomi Avraham). Their stories merge with the neighborhood Don Juan, working girl, blonde American tourist, the eligible doctor, the token gay man, street cleaners and undertakers, each unhappy in his or her uniquely quirky way. The hooker, the hunchback, Henia (wonderfully portrayed by Rivka Michaeli) who claims she hasn’t really lived since age 8, all march in a parade of misery and mediocrity, greeting each new day somewhat the worse for wear.

Whatever life does or does not bring to these characters, they can all look forward to the same thing: one by one the characters die, led out by the undertaker and followed by those still alive, who have come to mourn and gossip. When it comes to eulogies, well, what can you say?

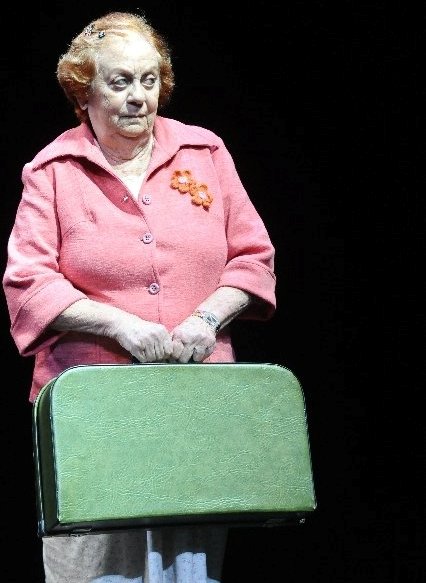

Ben Moshe is a prolific director; movement and the physical embodiment of character play a central role in all his works. The happy encounter between his interpretation of Bobeh Globchik, and the expressive talents of Hanna Maron is one of the great pleasures of this production. Without speaking a single line, Maron’s Bobeh is a rebel with a cause, joyfully escaping the clutches of one institution after another, returning to the arms of her somewhat less than loving family. Adding layers of narrative and complexity to her character each time she crossed the stage, moving from mischief to loss as she reaches the point where she cannot return home again. Her fierce desire to live and determination to live as she chooses, weave a thread of hope through the fatalistic fabric of the narrative. The image of Maron’s face shattered by the pain of parting from life is one of the most painfully beautiful moments of the play.

The end is known and equal for all, in the interim are small, insignificant people leading small insignificant lives, even their dreams are gray, yet somehow “full of desire.” There are no outstanding individuals here, no heroes and no happy end, yet no end to desire. Motke (Yoav Levi), caught between the needs of his pregnant wife, hunchback brother and the cost of living, exudes stress in every inch of his body, yet in his own not quite competent way keeps trying for something better, something more. Critical of the parsimonious to the point of meaninglessness of the eulogies delivered by Alphonse at the neighborhood funerals, after Alphonse goes the way of all flesh, Motke steps up. The succession of deaths and funerals gives him plenty of practice, as he tries to figure out how to do it better. When Henia dies, Motke begins in a fairly traditional way, describing the simple facts of Henia’s life as wife, mother, a good modest woman constantly complaining of aches and ailments. Yet stumbling on in his frustration, he insists, “There had to be something more to her than a fear of illness, things that went unsaid, a life that was not lived…God, you gave us funerals to remind us of our lives, let us not forget this cart and sheet between the funerals.” The end is known, but there is no end to desire, and there is something to say.

Suitcase Packers by Hanoch Levin, directed by Udi Ben Moshe, is currently running at the Cameri Theatre, check the website for dates and times.

Comments are closed.