They met in Paris last year: Anselm Kiefer, one of the leading figures in German and international art of our times, and Mordechai Omer, director and chief curator of the Tel Aviv Museum. Omer was then looking towards the opening of the new wing of the Museum and wanted to mark it with an inaugural exhibition of real artistic and spiritual value., Kiefer was interested, but didn’t agree to just another travelling display of his work. Instead, he proposed a show whose concept would be specifically tailored to this country. That is how Shevirat Ha-kelim – Breaking of the Vessels – was born, arguably the most powerful exhibition ever mounted at this Museum.

The sheer range and quality of the works on display impresses. Hung around the gallery perimeter are ten monumental canvases, as well as a trio of painted woodcuts. The central space is taken up by five sculptures from Kiefer’s Women of Antiquity series, and two site specific installations, the one that gives the exhibition its title; and the other, West-Eastern Divan, a multi-paneled, mixed-media painting under glass.

Wherever one looks in this exhibition, the eye is immediately held by the unorthodox materials that Kiefer consistently employs: ash, dust, straw, glass, clay, sand, plaster and lead, to mention only a few. Interviewed in 2001 about this aspect of his work, Kiefer stated that “whatever material I work with, I feel that I am extracting from it the spirit that already lives within.”

Almost all the works select for this show have biblical connections or relate to Jewish mythology, literature or the Kabbala – subject-matter that has increasingly occupied Kiefer’s attention in the last two decades. Yet, some paintings on view still give clear expression to the themes that Kiefer focused on previously. Born in Germany at the tail-end of World War II, he was the first and most prominent German artist to challenge his country’s amnesia as regards its charged past; and, during the 1970s and ’80s, his paintings and installations, performances, photography and artist books, referenced the Holocaust and the physical and cultural devastation wrought by World War II.

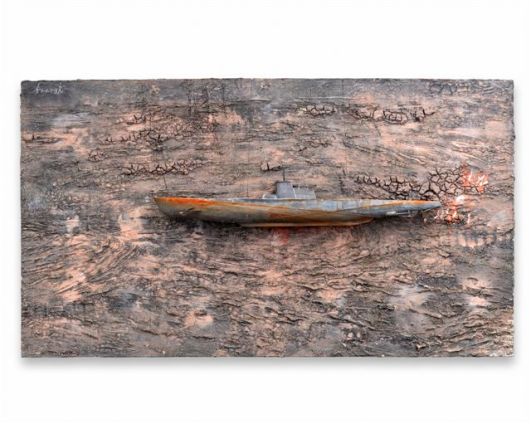

One example of this link with past themes is the striking landscape painting Ararat (2009). Its title refers to the mountains named in the book of Genesis where Noah’s ark came to rest after the great flood. In Kiefer’s version, Ararat is not shown, nor the ark. Instead a rusted submarine rests on torn branches and clods of mud. This image is a powerful symbol of destruction, surely bringing to mind the life or death sea battles that must have been fought between the German and British navies during World War II. The title of this painting, scrawled at its top left side, offers the only glimmer of hope in this desolate scene, since it was back to this mountain range that the dove, symbol of peace, carried the olive branch.

Warlike images appear in other paintings with biblical titles, among them the dramatic landscape Samson which has a rusted machine gun affixed to its heavily encrusted surface. It depicts a mountain with two window frames perched on its summit – frail looking objects that represent the gates of Gaza which, according to the biblical story, were uprooted and carried off by Samson. Palm fronds, perhaps representing nature and peace, spread out like wings from this painting on which, high up, Kiefer has chalked in the name Gaza. How to interpret this painting? Was it the artist’s intention to simply highlight a story in which its main character morphed from a warrior with super-human physical powers to a noble and spiritual person? Or does this painting, executed this year, have quite a different sub-text?

Underlying the creation of the installation Shevirat Ha-Kelim is a doctrine regarding the creation, destruction and restoration of the world. Originally formulated by Safed Rabbi (the Ari) Isaac Luria (1534-72) it remains a dominant part of Kabbalistic and Hassidic thought. In brief: the body is conceived as a vessel and the Divine Light contracted, once filled ten such containers. But due catastrophic upheavals in the world, these vessels have shattered and a state of chaos ensues, reversed only by a process of Tiqqun, or repair.

Kiefer has visually interpreted the act of the Shattering of the Vessels by constructing a library of sorts. Housed at the far end of a specially designed room, it appears at a first sight to be some kind of altar. On closer inspection, one sees that it consists of metal shelves supporting huge empty books constructed from lead. This edifice is pierced by shards of glass that are also scattered on the floor.

For Jews, this library may have painful historical connotations; Kristalnacht, November 9–10, 1938; for instance, or the burning of books on Bebelplatz Square, Berlin on May 10th, 1933, now the site of Bibliotek, Micha Ullman’s underground memorial.

Kiefer supervised the installation of this work. And his final task, prior to its completion (which can be followed on a video in the exhibition) was to draw spheres on the wall above this defunct ‘library’ and chalk in the words Ain Sof to denote the hidden, infinite aspect of G-d.

The other highlight of this show is West-Eastern Divan 2010, a work that appears to refer to the fragmentation of memory over time, and the eventual disintegration of living things. Its title is taken from a collection of poems by Goethe influenced by Muslim poets and poetry. Writing in German, he set out to capture the spirit of the East through sensual descriptions of flowers and plants. Kiefer’s interpretation is based on all these sources.

54 identically sized paintings are sited on two facing walls, 27 in rows of three on each side, no work is identical, all are delicate configurations of branches, seeds and pressed flowers set against a background of cracked earth and lead. Some panels include white floating shifts, like lost souls. The coloration is dissonant, conjuring up storms or fires, or just a pale or dark void.

In this work, Kiefer has found a way of ‘bringing’ the West and East together. To emphasize this unity, he has listed the names of Jewish and Muslim philosophers and poets on the same wall. As a catalog text suggests, the artist is reminding his public that “spiritual figures from both religions have sought through their writings to establish peace and bring tikkun to the world.”

To make one more point. There may be visitors to this exhibition who will look in askance at Kiefer, a non-Jew, for appropriating ‘Jewish’ sources for his art. But it is well to remember, like all great religions, Judaism is not an exclusive domain. And, as one sees here, Kiefer approaches his subject-matter with respect and restraint.

Earlier this year, not many months before the opening of the new Herta and Paul Amir building, Mordechai Omer fell ill, and senior curator Dr. Doron Lurie took over preparations for the Kiefer show. Omer died in June; and this magnificent exhibition is dedicated to his memory.

Lily and Yoel Moshe Elstein Multi-Purpose Gallery

Herta and Paul Amir Wing

Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Open till mid April.

WE ARE SO LUCKY TO HAVE A MUSEUM OF THIS CALIBER.

THE ANSELM KIEFER SHOW IS NOT TO BE MISSED….IT HAS A PROFOUND AFFECT ON ALL YOUR SENSES. WHAT A WONDERFUL ARTIST

Comments are closed.