Numerator and Denominator, the ‘mathematical’ title of a new exhibition at the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art should warn visitors that this is no ordinary event. Curated by a quartet of people from various disciplines, including poet and Professor Zali Gurevitch and artist Tsibi Geva, the show has no catalog. Instead, Gurevitch and Geva have written a book whose aim is to “turn attention to the vertical status of the world and its consequence on our times, our leaders, and our language.” The impression gained is that this exhibition serves first and foremost to illustrate their (Hebrew only) text.

The reference to the term ‘vertical status’ implies an upward/downward view of life, entities bisected by a horizontal line. As regards the title of both the book and the exhibition, the numerator comes to represent a number of equal parts while, below the fractal line, the denominator states how many parts make up a whole.

Luckily, this group exhibition has a life of its own. With 19 artists participating, including some well known foreign artists and Israelis working abroad, there are many impressive contributions: paintings, installations, photos and video pieces. All of them relate to some metaphorical aspect of the topic under discussion in the book, whether the concept of darkness vs. light, the material world vs. the spiritual, master and slave.

The concept of above/below and the ‘fractal’ line between the two, finds direct expression in the work of Be Andr (Norwegian-born, living in London) who treats words as images to explore the difference between reading and seeing. Pasted onto a white surface in large format are the letters IS, but only their lower parts are visible, the rest gives the illusion of having been cut off, or else obscured by the horizontal plane of the ceiling.

Darkness and underground places are the subject of a significant number of video works, starting with several by Vito Acconci, a New York artist and designer who was among the pioneers of video art. Claim (1971), one of two exhibited here, was one of his most confrontational performances. Blindfolded, armed with metal pipes and a crowbar, he sat in a basement, threatening violence to anyone daring to approach.

This piece is fascinating, not for its plot which is repetitive and boring, but for the fact that this work is part of video history. Its grainy and blurred images and indistinct sound are light-years removed from today’s sophisticated use of this medium. Acconci’s penchant for isolation is also evident in his design Sub-urb (1983), also on view. It features photos and sketches for an underground housing complex that he describes in one scribbled memo as “a place to be alone; a place for a place to be alone in.”

From confinement to freedom is the story line of Standing Here, a characteristic video work by New York performance artist Kate Gilmore. With her hair smoothly coiffed, wearing dress and gloves, Gilmour is shown forcing her way out of underground cell, hauling herself up by knocking leverage holes into the plaster walls. Like other of her documented actions, this particular scenario is a metaphor for the challenges and struggles still facing women today.

Tunnels are documented by several artists in works having social or political content. For instance, through texts and photos architect Yael Hameiri, explores the phenomenon of tunnels in Gaza on the Egyptian border; while Ron Amir records a journey through the Herodian canal that lies beneath Jisr a-Zarqa, north of Caesarea. His guides are Muslim youth living in a village on top of this site.

The digital photos taken by Yehudit Schreiber of another type of underground place are just superb. They were shot in an unlikely place, a little known laboratory situated in the Botanical Gardens of Tel Aviv University where studies are made on the root systems of plants. There, in a dark, six meter space, the roots grow above ground, suspended with no foundation, enveloped by droplets of water. These are the images she has photographed so successfully.

The concept of inferior/superior is illustrated in The Chief of Staff, an ironical, somewhat daring presentation by Itamar Gilboa, an Israeli living and working in Amsterdam. Prof. Patrick Healey, commenting on an earlier version of this piece, stated that it would be ‘difficult to imagine an exhibition in which an artist could place himself more directly on the line, so clearly in sight.”

161 small paintings are on exhibit. They are attached to a netted wall and represent in hieratical order the make-up of the Israeli military, its arms and ranks, identified by titles and colors. Each small picture shows a figure with wings – perhaps a hero or fallen soldier- since the chests of some angels are pitted with bullet holes. Above, in all his glory, the chief of staff is surrounded by golden clouds.

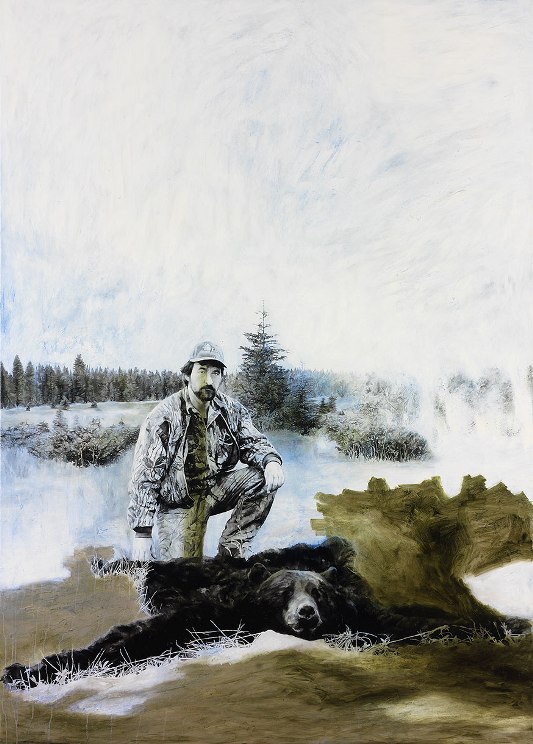

Domination of man over creature is the topic illustrated in Anat Betzer’s large oil painting, conceived in a wintry palette, depicts a hunter standing guard over a dead bear. Her other four paintings, all based on photographs, point to attempts to dominate the landscape through the construction of military bunkers. Eventually, as one notes in these paintings, after years of disuse, Nature has apparently triumphed, overgrowing these structures so that mere traces remain.

Two works in particular manifest a yearning for the transcendental. One of these, View from my Kitchen Window (2008) by UK artist Julian Opie, is a beautiful minimalist landscape built up from digitally manipulated photographs. This is not a constant image, its geometric lines and the colors of land, horizon and sky altering according to the time of night or day. When one remembers that the painter Monet took two years of painstaking work to produce 31 versions of the façade of Rouen Cathedral in different lights and weather, one cannot but marvel at the way that computer animation technology, as employed by Opie, can conjure up ‘paintings’, albeit of a different sort, in a far shorter space of time.

Efrat Vital offers a striking video piece comprising footage photographed while driving under bridges on the coastal road. With the camera aimed at the sky, one’s view towards the heavenly and unattainable is continually interrupted as the vehicle she is travelling in passes under successive bridges. Central to the show’s theme, her imagery, a metaphor for the earthly vs. the sublime, provides a fitting ending to this review.

This exhibition, also co-curated by Tal Bechler and Museum director Dalia Levin, is open till September 10th.

Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art,

4 Ha’banim St., Herzliya. Tel 09. 9551011

Title

A Modest Proposal: A Campaign to Convince the Herzliya Museum of Con temporary Art to feature the Washerwoman in its New Exhibition

(campaign slogan–“Guinness is good for you”

I read Thoreau one hot day a long time ago and went to the pond at Walden to see for myself how it was in the woods. When I discovered that being a tent person did not involve skinning squirrel, I was reassured. Thoreau took his meals a local inn every day. When I discovered that during the two weeks he spent in the woods by the river, his mother did his laundry, I was intrigued. I turned my attention to washerwomen and like those fortunate or unfortunate people who find themselves under the influence of a certain kind of mushroom, I soon began to see them everywhere. Their services were needed in particular in those places that saw themselves as Promised Lands. Ireland has loads of them; they flourish here and in Paris–particularly in the Jazz Age–like Liliths of the Veldt. Since the washerwomen of the world must, I imagine, have few illusions about how whiteness is achieved and are not afraid of dirt, they are admirably qualified for a position in this Exhibition. What kinds of questions does the exhibition raise? Is it not first and foremost about dirt? Does it not suggest that we go back to the crossroads of history and consider from a relativel safe hight art position the road not taken, en route to the PL? Does it not ask us to imagine, to think in terms of what if? I hereby nominate the washerwoman for the position vacated–as this exhibition seems to suggest–by the long dead God of Genesis. Ah, but you say, does she speak Hebrew? Well, like all tent hoisting followers of the washerwomen, I look at these installations and I see a mother tongue that we all know, not Irish or Hebrew, but a jazz language. One nomad, trapped in Jazz Age Paris during the war pictured this realm between darkness and light as at once a mother-tongue and as Guinness (the black brew with a white top recently drunk by the Obama in his ancestral home in Ireland). Of course, Guinness was delighted with the free advertising windfall, but as an image of an Everyman trying his best too to make a home in homelessness, it could do worse. . . Joyce, the man who spent much of his life rewriting Genesis as the new book of guinnesses, would have laughed to see the engine of global capitalism and the American political machine making visible his dreams of a new Ark, a Porterboat.

I, who am old enough now to know that I know nothing, believe that fear will always be with us because we need it to keep us alive. Benjamin said that the disease of our age is the need for certainty, but how can we live without certainty of some kind. It is not so easy to live without the illusion of life as a journey towards the Light. Can we learn from “high” art exhibitions like this one? Does this art include the voices of the washerwomen of the world and the voices of children? Who was that Hebrew poet who wrote for childen and used images of a child on a see-saw? He said we hide even as we seek. I laughed when I saw this because I recognize that this way of seeing he spoke of, this child-like self-trickery; this language of revealment and concealment, of hiding and seeking, of darkness and light, is my mother-tongue. I am already black and white. Because something in my evolutionary memory knows home is hume, dirt, I cling to the “home” offered by the script of Genesis, in all of its modern manifestations. I build boundaries in my tent-home by the river. . . . Yet, like a child learning to walk, in tiny, almost invisible stages, I unpick with images, not words, the hold Genesis has on my mind. I find myself, when I look, working like a mole underground to rework myself from within, to dissolve boundaries between all my Egypts and all my Promised Lands, struggling to transform Genesis into my very own new book of Guinness. On a daily basis, I admit, on the river banks of my own aspirational jazz nation, up to my eyebrows in water, I get massacred and end up as usual covered in dirt.

Still, it is summertime and the catfish are out there somewhere. . . .

Q

Comments are closed.