“I am a memorial candle.” This is how Haim Maor, artist, curator, writer and educator, described himself at the opening of his new exhibition at Tefen which represents three decades of work on themes stemming from his childhood experiences as a second-generation Holocaust survivor.

For many reasons, critics are wary of addressing art of the Holocaust. In fact, many artists themselves tiptoe around this topic, opting for metaphors and symbols. But Maor tackles his subject-matter matter head on. Yet his art is not introverted. In fact, it could be compared to a tree, its roots buried deep in his life-history, but its branches and leaves reaching out to our collective thoughts and emotions as Jews and Israelis.

A huge gallery, once a factory warehouse, is the ideal space to house the large number of paintings, prints, photographs, ready-mades and mixed media installations that make up this show. Unfortunately, apart from a short statement at the entrance, visitors to Maor’s exhibition are left overmuch on their own. There are no texts or even a word or two to enlighten one as to the ‘right’ place to start, the ‘ best’ route through the show, or the different themes that develop. .

If there had been a heading the first space might well have been titled ‘Haim’s Room,’ since the objects in it relate to his childhood memories of his parents Malka and David Moshkovitz. Holocaust survivors from Poland, their home was in perpetual mourning for lost family and friends. Adding to the weight of this burden on a child was the fact that Maor was named for his paternal grandfather Rabbi Haim- Benjamin Moshkovitz, murdered in the Holocaust. Several of his paintings reflect his belief that he has been followed throughout his life by a double or a shadow.

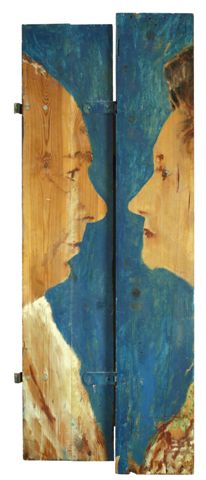

At the center of this first ‘room’ is a fiberglass cast of the artist by sculptress Ofra Zimbalista. He stands in a bath-tub, head downcast, in a humiliating pose that recalls Holocaust photos of nude Jews lined up for punishment or murder. On the walls behind are paintings he made of himself and his parents from the late 1980s. In one, the face of a youthful Maor abuts a yellow Star of David; in another, the heads of his parents, almost touching, are turned towards each other. This double portrait, in company with many other paintings on display, is executed on rough, non-aligned planks of wood that project a sense of disquiet or dysfunctionality. In other instances, slats are actually missing promoting the idea of loss or absence.

Collections of photos are affixed to the wall. Snapshots of family members who perished are interspersed with black squares and hung alongside blurred negatives of other faces. Several works in this section also illustrate the legend of the Mark of Cain, the first-born son of Adam and Eve forever cursed for murdering his brother; the allusion possibly being that Maor sees himself as cursed by the memories and experiences of his parents.

The story of Maor’s parents supplies the theme for the adjoining space. One might at first get the impression that the objects on display are genuine historical documents, but this not the case. The images and objects were selected to conjure up the horror of the Holocaust and the life-long suffering it imposed on the survivors.

Hanging alongside a black painting of the watchtower at Auschwitz where Maor’s father was incarcerated, are more portraits of his parents, in this instance showing their features in stages of obliteration. Two wall works make a strong impression: one of these is a delicate blouse belonging to his mother. Suspended in a light box, this garment takes on a ghostly character – “I had white blouses,” she once told her son, “with lots of white lace that my father bought me at the fair.” The other object on view is the battered suitcase that Maor’s father brought with him to Israel. Maor has pierced holes in its surface so that they form the number 78446 that was stamped on his father’s forearm. With a light set inside the case, this object too takes on an ethereal aspect. This concentration camp number surfaces again and again, overlaying pictures, texts and photographs in all parts of the exhibition.

At the centre of this space small objects and family photos are arranged on the first of five Set Tables. In this instance, a central sunken area is filled with memorial candles, a sight that accords with Maor’s childhood memories of the eve of Yom Kippur when his mother would pack the kitchen sink with lighted candles in memory for each of their lost loved ones and others who perished in the Holocaust.

Featured in the adjoining rooms are paintings and photos of the Maor family, children and grandchildren. Again, the paintings are on wood, and again the slats are badly fitting. Some of his friends are also depicted. They wear masks or other eye-coverings prompting questions regarding concealment or disguise. Also included in this group, is a painting of St. Lucia, patron saint of the blind, depicted in art as holding a dish with two eyeballs laid upon it. This image, and many others, illustrate Maor’s next major theme: loss of vision.

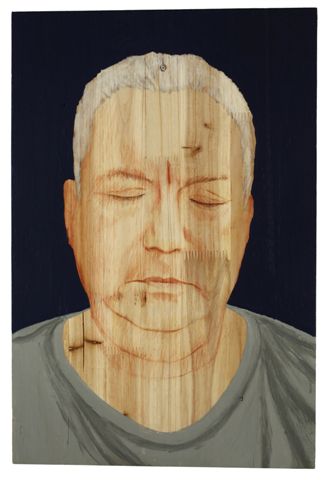

This is a subject with which Maor is well acquainted. His maternal grandfather Ephraim Rutter survived the Holocaust but was blinded in Poland by Nazi thugs; and as a young boy Maor was his constant helpmate and Seeing Eye, and companion in the synagogue. Empathizing with the subject of blindness, while also relating to the overall title of this show – They are Me – Maor paints not only his blind grandfather but a set of self-portraits in which he depicts himself with closed eyes or blind spots covering his face (his forehead also bears the Mark of Cain). The inference here, if one understands Maor’s work correctly, is not just to physical blindness but to mental blindness where intentionally, or unintentionally we ignore subjects that we don’t’ see or want to think about.

This theme also links up to the two final spaces in this exhibition. The first, Susanna’s ‘ room,’ touches on the complex subject of forging relationships between Israelis and young Germans whose parents or grandparents may have been guilty of terrible crimes. Maor’s approach to this subject is centered on Susanna, a German Christian who volunteered at Maor’s kibbutz in 1986, and became a friend of his family. After she left, he went, with her permission, to Germany to research her family background, eventually discovering that her grandfather had Nazi connections.

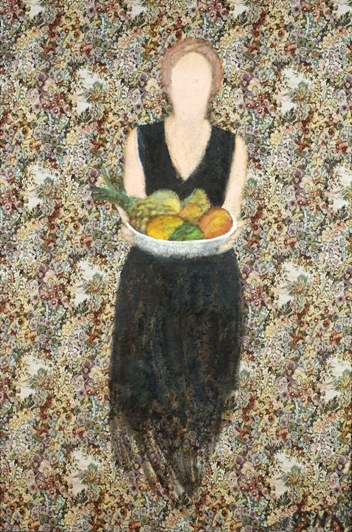

For the next 15 years Maor photographed and painted Susanna, resulting in the exhibition Forbidden Library (1993-4) shown in Israel and Holland. In one rendering, on display here, she and Maor face each other across a black void; in another, her painted profile is progressively obscured. Maor also paints her full length several times. In one composition, painted onto Gobelin tapestry (representing European bourgeois taste?) she is depicted, face blanked out, proffering a bowl of fruit, perhaps as a peace offering.

Objects chosen for the set table in this space range from a classical sculpture of a woman’s head to a photo of Susanna’s grandfather in Wehrmacht uniform, set alongside one of his blind grandfather. By this means, Maor is apparently trying to fathom the paradox between the noble traditions of European culture and the bestial behavior of the Nazi generation. But, in addition, it also seems clear from his obsessive treatment of Susanna’s image, that he understands that their two life stories have elements in common. Both of them grew up in homes where, for different reasons, secrets abounded, and certain subjects were taboo. They are Me.

Finally, there is Haim and Khader’s ‘room.’ A space shared by an Israeli and a Palestinian, both of whose names begin with the Hebrew word khet associated with the creation of life. A video film documents the close friendship that has developed over the years between these two artists based on their determination to set politics and bitter memories aside and make art together, each painting the other’s portrait. Celebrating their closeness is the final Set Table. It is laid out for a shared family meal. There are 12 place settings, likenesses of individual members of the families of Khader Oshah and Haim Maor painted onto porcelain plates: They are Me.

This is a richly rewarding exhibition, albeit painful in parts to view. In years past the content and style of Maor’s art have come in for criticism for its autobiographical nature, its theatricality, and mixture of viewpoints and materials. But today, all these aspects of his work are perfectly in tune with the multi-faceted character of contemporary art.

The exhibition is accompanied by a substantial book-catalog that includes fine photos by Avraham Hay, a clutch of texts by distinguished scholars and writers, and a written record of an important conversation that took place recently between Maor and Ruthi Ofek, the exhibition’s curator. The show will remain at the Open Museum, Tefen, till January when it will move to its sister Museum at Omer, near Beersheba.

Visiting Times: Sunday – Thursday 9:00 AM– 5:00 PM, Friday and holiday eves, 10:00 AM- 2:00 PM, Saturday and holidays, 10:00 AM – 5:00 PM. .

Excellent article which I will take with me when I visit the exhibion.

Ecellent article which I will use when I visit the exhibion.

Comments are closed.