It’s always sensible to approach cultural histories with caution; as someone once said about the decade of flower-power, the pill and the first summer of love, if you remember the 60s then you probably weren’t there. It’s not just the detail that matters, but the temptation to create an after the fact narrative, pulling together the loose ends of an era into a grand unifying theory, with answers to all the relevant conspiracy theories of the era chucked in for good measure.

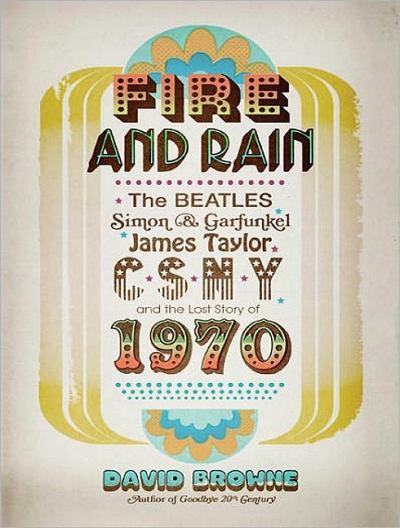

To be fair, Fire and Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, CSNY and the Lost Story of 1970 doesn’t go near the latter. What author David Browne does propose, however, is that 1970 was the lost year: “the moment when the remaining slivers of the idealism of the 60s began surrendering to the buzz-kill comedown of the decade ahead.” Perhaps. But behind great theories like this always lies a subjective subtext; Browne admits as much when he says that the idea for the book from a suggestion to “write about the music I loved in my childhood.” And what would that be? Why, The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel…at least we get this out of the way right at the beginning. Caveat emptor: if this music is not your cup of tea, then you might want to look for a comprehensive parsing of the end of the 60s elsewhere.

But this is a bit unfair. Browne does get a lot of things right in his mise en scene. 1970 was a troubled year in America’s social history. The country was up to its knees with the Vietnam quagmire; the optimism of the civil rights movement had been replaced by the sullen aggression of radical groups like The Weathermen. Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew were spearheading the charge against dissenting political voices, under the guise of maintaining social order; the dream of the Age of Aquarius had begun to collapse under the weight of unsustainable expectations and drug overdoses.

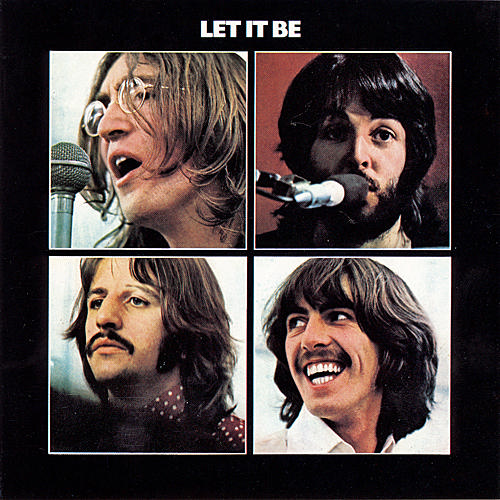

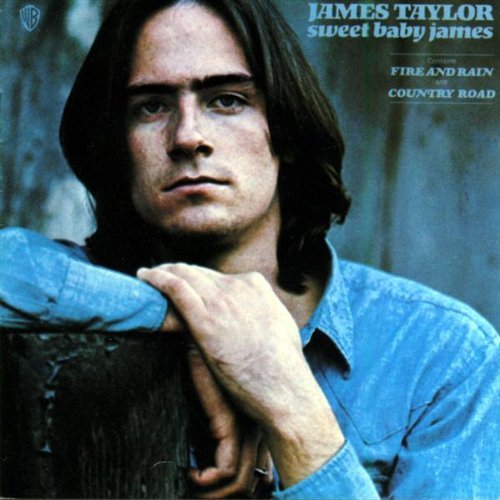

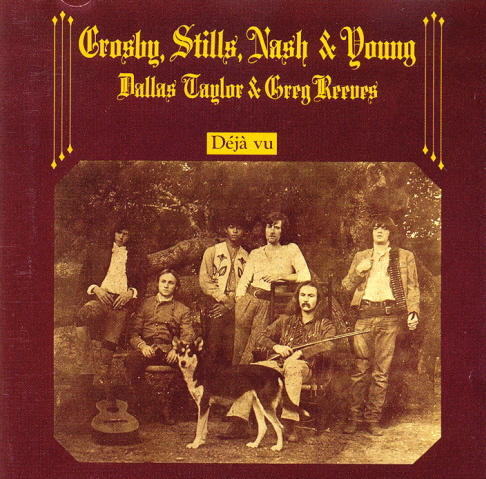

Compared to the hedonistic offerings of the last few years, the music of 1970 had achieved a new maturity influenced by the social dysfunction of the age, Browne argues convincingly. The Beatles were at their apogee (although on this point, a little more later); Simon & Garfunkel produced their magnum opus, Bridge Over Troubled Water. Folk rockers Crosby Stills and Nash recruited the truculent but remarkably focused Neil Young to their number, and produced Deja Vu; a smoldering young singer-songwriter called James Taylor shook off the deleterious effects of drugs to record his breakthrough second album, Sweet Baby James.

Browne charts the course of a turbulent year with a steady hand, the chronological account of a year in the life of his subjects offering up a remarkable stream of anecdotes and overlaps between the principals. Who knew, for instance, that Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel didn’t recognize the iconic qualities of the lead track of their 1970 album? Or that Simon worried about it sounded too much like The Beatles’ Let It Be – or that both Simon and Paul McCartney had considered offering their songs to Aretha Franklin to record? Or that Neil Young only played on half the songs on Deja Vu, one eye already on the exit door?

But what comes through more clearly is the turbulence of the era. When Browne describes the cover of CSN&Y’s Deja Vu as feeling “like America had been in a civil war”, he puts his finger on the button. There’s no doubt that the tensions of the moment percolated down into the music – CSN&Y’s magnificent Ohio, for instance, was written by Neil Young as a direct response to the Kent State shootings of 1970.

Likewise, one might suggest that the fractious relationship between The Man and The People filtered into the intra-band relations. They all seemed to be at war: McCartney against the rest of The Beatles, James Taylor against himself. Simon and Garfunkel had never quite figured out a way of containing their immense egos within a single album. As for CSN&Y? The supergroup pretty much held itself together with sticking tape, contractual obligations and lawyers’ threats.

As a straight biography of a very interesting year, Fire and Rain is very good. Browne did his research, and did it well. There are moments when one almost feels in the heart of the action, so vivid are his descriptions. And the way he describes it, 1970 must have been one hell of a year. I mean, on one summer’s night in New York, you had Simon and Garfunkel AND Jimi Hendrix headlining on separate bills. What more could you ask for?

But his grand narrative is – to this reader at least – on shakier ground. Browne proposes that the four albums produced by his principal that year – Let It Be, Bridge over Troubled Water, Deja Vu and Sweet Baby James – marked the end of a period of innocence, an awakening to the harsher realities of 70s candor and realpolitik over 60s optimism and hippy love. Kind of. The book has a lot of revealing side detail – like the fact that the truncation of the draft to just 19-year-olds undercut the protest movement at one go, self interest trumping principled objection to the war.

But as for the music? Deja Vu is great, but Neil Young’s two succeeding solo albums, After The Gold Rush from later that year and 1972’s Harvest, are arguably more accurate weather vanes of a changing age. And as for the Beatles’ Let It Be? The only dysfunction it reflects is that in the imploding Beatles – which, oddly enough, Browne records in precise detail. One can blame Paul McCartney for lots of things, but he was right in thinking that Phil Spector ruined a perfectly serviceable album with layer upon layer of schmaltz. In any case Abbey Road – technically The Beatles’ true last album, in that it was the last that they recorded – knocks the socks off Let It Be. (This may not be a fully objective assessment, admittedly.)

This aside, one must be warned that Browne goes into the musical detail of the age with the zeal of a genuine fan. Fire and Rain is not for the faint of heart; it isn’t ever wholly trainspotter-ish, but the wealth of detail may overcome the casual cultural historian. This shouldn’t put one off, though. That aside, there is something else. Fire And Rain – unconsciously, I think – highlights quite a few parallels between 1970 and 2010: an unpopular foreign war, the encroachment on civil liberties, the fear of domestic terrorism, the end of a hedonistic age. 40 years from now, I wonder who will be picked out as the troubadours of our troubled age? I can’t for the life of me imagine. But I hope that when they are chronicled, it’ll be as much fun – even in a contentious way – to read about them as it was to read Fire and Rain.