With the opening of Interiors , the 500th exhibition to be mounted at Jerusalem’s Nora Gallery, the oldest existent in the country, it is more than time to pay homage to its founder Nora Wilenska (1899-1980). But much credit is also due to her daughter Dina Hanoch who, for the past 30 years, has continued to display her mother’s superb collection of European art dating from the early to mid 20th century.

The gallery, operating on a non-commercial basis, opened in 1954 in the gemütlich surroundings of Nora’s modest flower-filled apartment in Rehavia where it is still based today. In the early decades of the State, Nora and her gallery were one of the hubs of cultural life and a favorite stopping-place for Jerusalemites out for their Shabbat stroll. Among the gallery’s aficionados were immigrants from Austria and Germany, many of them artists who formed a tight-knit community in the city.

It is perhaps forgotten today, that for the first few decades that Nora ran her gallery there was little contact with art and artists outside this country. Knowledge of developments abroad was almost totally gleaned from postcards or picture books brought in by the occasional visitor. So, the original works that Nora showed in her gallery would have been of considerable interest to the local art community.

But times have changed. Jerusalem has changed. And so has the art scene in a city now dominated by well publicized shows at the Israel Museum and exhibitions held at Artists Association House where every member regardless of his level of attainment is entitled to a solo show. And the outlook of Jerusalem artists is also different. Most of them want to exhibit in Tel Aviv galleries, or show their work abroad.

In short, The Nora Gallery located in a quiet backwater of the city, no longer receives the attention it deserves. Nevertheless, Hanoch continues to plan and show high-quality themed exhibitions or else one-person shows, culling her material from the gallery’s Museum-quality collection and/or from the work of selected contemporary artists.

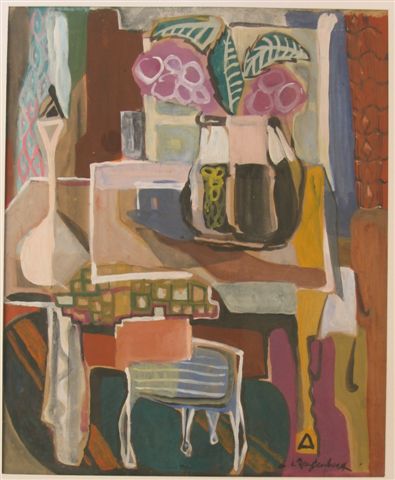

20 artists are represented in the current group show. But because the works adhere to a theme, as most of Hanoch’s exhibitions do, this means that we are not necessarily seeing an artist’s best or most typical work. This is the case with an early still life by Fima (Efraim Roytenburg) who had his first exhibition in this country at the Nora Gallery. Born 1914 in Harbin, this artist studied and taught painting in Shanghai before moving to Israel in 1949. Some ten years later, he settled permanently in Paris.

The Fima ‘interior’ that Hanoch chose to exhibit dates from 1956. It is a beautiful work but it is only a precursor of the mature abstract style synthesizing Eastern and Western traditions that Fima would perfect in Paris and gain him an international reputation. In this particular piece there are only hints of what was to come: a full spectrum of luscious colors, a paring down of semi-abstract shapes and the occasional calligraphic brushstroke.

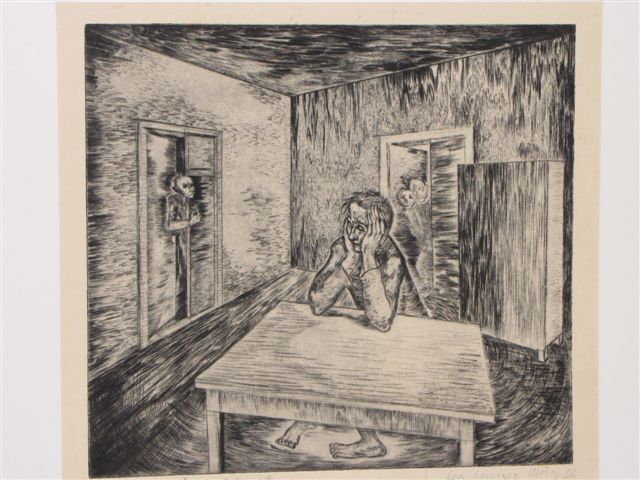

Dina can recount many stories about the artists. One concerns the Dresden-born Lea Grundwig (1906-1977). Looking for fresh material to show at the reopening of the gallery after her mother’s death, Hanoch came across a portfolio that she had never seen before. It contained drawings and prints by Grundig, a prominent member of Jerusalem’s art community in the early 1930s. Hanoch relates that after the war, learning that her husband had survived internment in a concentration camp, Grundig moved back to East Germany to be with him. Many Jerusalemites, including Nora, saw her decision as a kind of betrayal, and this was most probably reason why her works were not shown in the gallery for many years. But Hanoch, impressed with the power of what she saw, decided to include drawings and prints by Grundig in this upcoming exhibition. Their display aroused enormous interest, and attracted visitors from around the country who brought with them information and catalogs concerning her later work. .

With this story as introduction, Grundig’s ‘interior’ turns out to be both strange and disappointing. It is a black and white etching that depicts a man (a prisoner?) seated at a table in an empty room (cell?) A head looks round one door, while a skeletal figure stands at the other. While this writer has not seen Grundwig’s work previously, she takes it for granted that this was a typical piece, since it accords to the artist’s description of her own work as expressing “a thousand fears, the presentiment of doom, imprisonment and inhumanity.”

All the artists who exhibited in this gallery became friends with Nora. Prominent among them was Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) who pioneered the Orphism art movement noted for its use of strong colors and geometric shapes. (Examples of her work are not included in the exhibition but can be found on permanent display in one of the rooms in the gallery).

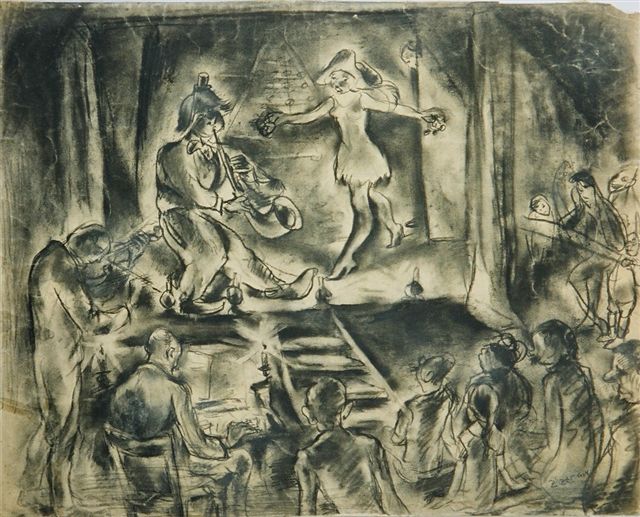

Another personal friend was Mary Fuchs, the widow of Gyula Zilzer (1898-1969,) a Budapest-born artist who was sufficiently well known to merit an obituary in the New York Times. After his death, Fuchs brought all her husband’s paintings and prints to Israel, requesting that the majority be sold to benefit the work of the Friends of the Bezalel Academy.

For this show, Hanoch has dipped into the gallery’s collection to select a virtuoso drawing by Zilzer. It depicts the interior of a night club, a subject that attracted so many European artists in the first half of the 20th century, in particular the German Expressionists with whom Zilzer was associated. Here, as in scenes painted by Expressionist Otto Dix and others, he introduces grotesque elements into his portrayal.

Olga Kundina and Eli Shvadron are among the contemporary artists who contributed to this show. Both of their works look back to the past; Kundina to German expressionism with her vigorous drawing flooded with red paint of café life in Rosh Pina; and Shvadron to a series of paintings of adolescent girls from the 1960s by the Polish-French artist Balthus. In particular, Shvadron has based his version which is pleasant enough on Balthus’ Three Sisters (1964). But it lacks the erotic dimension of the original.

Nora Gallery,

9 Ben Maimon Avenue

Jerusalem

Open Sun- Thurs. 4.00-6.00 pm; Sats 11.30am -2.00pm and by appointment O2- 5632849