Humor, or at least a light-hearted approach, is generally associated with comics. Yet this quality is almost totally lacking in the representative selection of 20th and 21st century comics and animation films on show in Visual Words – Comics from China, part of a cultural exchange program between Israel and Switzerland, and the Cartoon Museums of Holon and Basel in particular.

As many of the works in this exhibition illustrate comics were effective propaganda tools in China from the time of the establishment in 1949 of the People’s Republic under the leadership of Mao Zedong till the end of the Cultural Revolution (1976). During this era, professional artists working as salaried staff in Government controlled publishing houses produced comics whose storyline either discredited the old way of life or else educated a mainly illiterate rural population in the aims of the New Society.

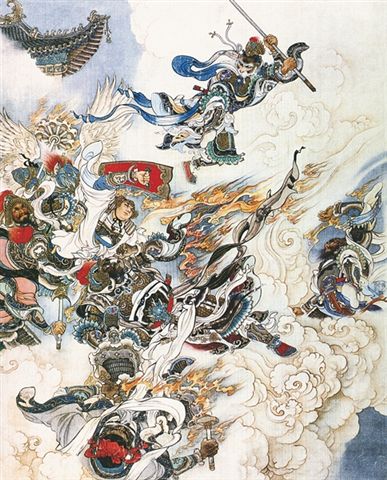

Hung in the first of three sections are comics by artists whose subject-matter derived from Chinese literature and folklore. One of the most talented was Liu Jiyou (1918-1983) whose graceful style combined the poetry of traditional Chinese painting with elements taken from Western art.

Commotion in Heaven (1956) is a typical example of his work. This illustration is based on the 16th century classical Chinese novel The Journey to the West in which a Buddhist monk, aided by Monkey King, an iconic Chinese character, sets out to collect sacred scriptures from Buddha in the Western Paradise; his purpose being to save the people of the lands of the South from “greed, hedonism, promiscuity, and sins.” In Maoist terms, the story of these characters, their conflicts and achievements as ‘told’ by Liu Jiyou were metaphors for the ideological struggles taking place in China at that time, as well as the better life envisaged by the Communist regime.

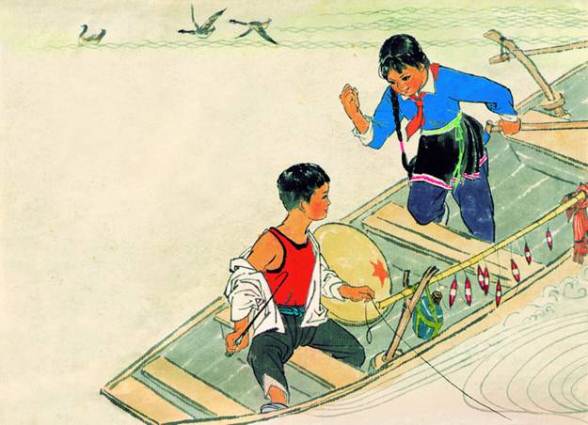

A realist style of depiction is common to the comics showing in the second part of this show where many of the works depict life in rural communes (perhaps produced for the enlightenment of city folk who never left the cities.) Drawings in black and white emphasis the harshness and drabness of communal living. However, a standout piece How to Catch a Sturgeon by Du Wei (1973), is realized in bright, crisp colors in the form of a New Year Greetings card. At first sight, this seems to be merely a naïve scene showing two child officers of the Red Guard trying to catch a giant fish. But this cartoon has political and educational message pointing out the value of people working patiently together to achieve a joint aim.

As curator Uri Bartal writes in his catalog text, a new era in the creation of Chinese comics began in 1980s and ’90s, corresponding to economic growth in the country, the rise of a middle class, globalization and an outward-looking policy. Artists began to produce light-hearted cartoons of life in the city or romanticized pastoral scenes. At this time European comics entered the Chinese market, but they were not greeted with enthusiasm. It was Japanese comics and animation films –Manga and Anime – that became – and still are – overwhelming popular in China. Local artists now imitate this style which is influenced by Japanese calligraphy and painting and where the characters express their emotions by means of their huge almond shaped eyes with glinting highlights.

One of the most successful young artists working today in this field is Xia Dia whose delicate Manga cartoons are sought after both in her home country and in Japan. What the Master Didn’t Say, is a typically romantic piece. It tells the story of a nine-year old child and her parents coming to live in a strange and beautiful place where they explore the wonders of Nature.

The subject of this exhibition will undoubtedly be foreign to most visitors, making the wall and catalog texts essential reading. But save for the captions, the written material is only in Hebrew. Once upon a time in Israel this was acceptable, but not today. If this venue who like to shake off its provincial image and attract the same public (including visitors from abroad) that comes to shows at the nearby Design Museum then bi-lingual texts and wall explanations are mandatory.

A footnote. Work is about to start in China, at Hangzhou, South West of Shanghai, on a Comics and Animation Museum. Designed by the Dutch architectural firm MVRDV, the building will be in the shape of eight outsize speaking balloons (as used in cartoon format). The plans are certainly worth looking at:

Israeli Museum of Caricatures and Comics, 61 Weitzman St., Holon

Tel: 03-6521849

Till November 17th 2012