At first blush, the choice of Luchino Visconti’s 1954 film Senso to open Another Look – the Restored European Film Project #1 – presents as slightly curious. There’s no doubting its artistic pedigree, of course: the story of lust, vanity and betrayal translates well today, the lush quasi-operatic setting of Venice and its environs still pleasing to the eye. But a film set within intra-European hostilities – the tail end of the Italian-Austrian war of unification, to be precise – could be interpreted as mirroring perhaps a bit too closely the tensions that define by the European Union at the present time.

To be fair though, that would suggest that Another Look is concerned primarily with propagating a particular image of the European Union, which is probably not the case. Rather, the festival of restored cinema classics, running throughout January at the Haifa, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv Cinematheques, seeks to “raise awareness to both classic European cinema and the means by which it is preserved.” A collaboration between the European Union and the embassies of the ten participating embassies in Israel, the underpinning proposition is much less dogmatic, more philosophical: looking back at how the past has shaped our identities is a useful means of considering where the future might take us.

Split into two thematic overviews, the selection of films gives a rich, diverse historical context to the evolution of a collective European identity, a reminder that cinema often serves an important function as the prism with which we can diffract and make sense of our times. “Band of Brothers,” the first theme, focuses on the attempts at defining a community in Europe. Not a straightforward endeavour, as two world wars and numerous internecine disputes testify. But unity is often borne from strife; there is a useful reminder here, not only that the turmoil of the present age is not unique but also that these things can, and will pass.

The second thematic grouping, “From the Mouth of Babes,” feeds directly – in a metaphorical sense – from the first. Think of youth and youth culture as the weather vane for future preoccupations; invariably accurate, invariably threatening until viewed in retrospect.

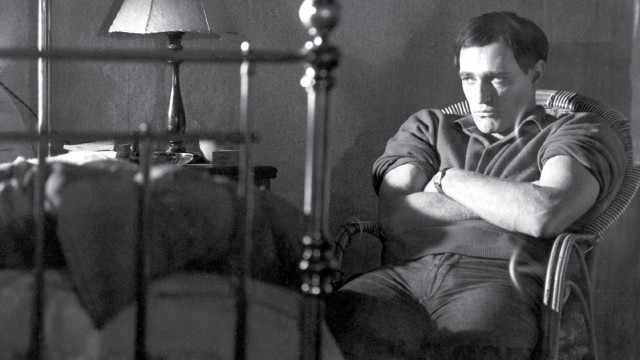

There is a surprising pleasure in revisiting some of the classics of the past and measuring them against the cinematic preoccupations of the present age. This Sporting Life, Lindsay Anderson’s multiple Oscar-nominated offering from 1963, presages the contemporary conduit of sporting celebrity as an escape from the monotony of working class life with remarkable acuity. Richard Harris’s brooding presence as the local hero done good through professional rugby may perhaps be less sensitive, less politically correct than if shaped today (as an aside, one cannot but think that the principal flaw with Clint Eastwood’s Invictus was that he never quite succeeded in evoking the relationship between Rugby and Afrikaner culture). Even so, the tensions that underwrite the ultimately tragic relationship with Rachel Roberts’s widowed Mrs Hammond resonate still.

On a different tangent, Jiri Menzel’s Closely Observed Trains – winner of the Best Foreign Film Oscar in 1966 – presents a bleakly humourous take on life in Czechoslovakia under Nazi occupation. Milos looks forward to emulating his forebears – idlers to a man – as he takes up his first job as a station assistant. Like youth across the ages, his primary preoccupation is with all matters carnal, a state of affairs encouraged by his supposedly elders and betters at the train station. It is a curious construct, but conveyed with a realistic ease. That the erotic minutiae of the moment takes precedence over the political concerns is the case not because it is more important, but because it happens to be more immediate.

And that’s the thing about immediacy that came to mind whilst watching Senso on the opening evening of the festival. The haughty Italian countess Livia gives way to unmediated urges, falling for Mahler of the occupying Austrian army. No good will come of the self-destructive impulses that impel the two; not because love between the two is not necessarily possible, but because neither pause long enough to consider the implications of their actions, for themselves and for others. It is the small details that give an added poignancy to the great events of our time. In much the same way, one supposes that the individuality of the films that make up Another Look will offer a deeper, more intimate appreciation of the social commonalities that underpin the European political project.

Another Look: The Restored European Film Project #1, showing at the Jerusalem, Haifa and Tel Aviv Cinematheques through 31st January. A full schedule is available at www.anotherlook.co.il