Currently showcased at the Tel Aviv Museum is a selection from the Museum’s outstanding collection of 150 prints by Edvard Munch, gifted by Charles and Evelyn Kramer of New York. Introduced into the same space are works by three Israeli artists who have entered into dialog with the Norwegian master.

As a printmaker of virtuoso skills, Munch manipulated line, texture, color and pictorial details to bring new meaning to motifs and images derived from his paintings. His themes in both media were universal human experiences: death, alienation, anxiety, jealously and love. In contrast to the depressive character of many of the works on show, there is at least one that stands out for its radiant beauty: a colored lithograph titled Madonna (Loving Woman, Conception) depicting a nude, eyes closed, a halo above her head (and is that an embryo in the corner?). Munch was not a religious man, but nevertheless, he may have been aiming here to represent Mary, mother of Jesus, in the act of divine intercourse.

Most generally, fear and distrust marked Munch’s attitude to women, perceiving their role in life to “seduce, entice and deceive”. In several prints, he renders them as vampires, red-haired women sucking the life blood out of men. Also, as was in vogue among certain 19th and early 20th century artists, he concocted erotic myths in which animals play a major part. Picasso had his minotaur (part man, part bull), Munch’s women play with serpents and beasts as in the Story of Alpha and Omega, 22 lithographs illustrating a prose-poem written by Munch (they are hung near the gallery entrance.)

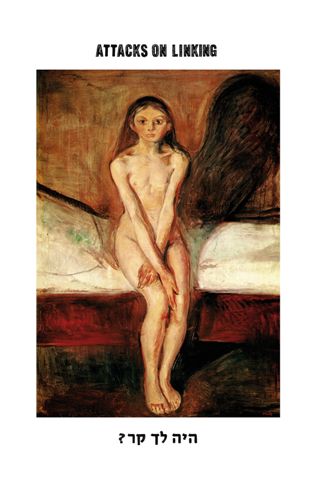

The psychological and emotional depths of Munch’s art, the story lurking behind what is visible are aspects of his work for which Israeli artist Michal Heiman has a clear affinity. For decades she has investigated the psychological processes involved in interpreting art and photography. On display here is a mixed media piece that she showed at the Tel Aviv Museum in 2009, its title Attacks on Linking taken from a 1959 article by Wilfred Bion, a British psychoanalyst relates to the malfunctioning of emotional and thought processes.

The source of Heiman’s offering is Munch’s painting Puberty (his etching of the same scene hangs on an adjacent wall.) Featured is a nude adolescent girl, seated on a bed, legs pressed together. A dark shadow looms over her. The meaning of this scene, like so many of Munch’s works, is unclear and depends on the viewer’s thoughts and emotions for its interpretation. Does it symbolize a young girl’s fear at her awakening sexuality or are we witnessing the prelude to a rape?

By scanning this painting from a reproduction in a book and then subjecting it to digital manipulation before printing it onto shiny photographic paper, Heiman has reinvented this scene, introducing into it her own prosaic question: Were you Cold?

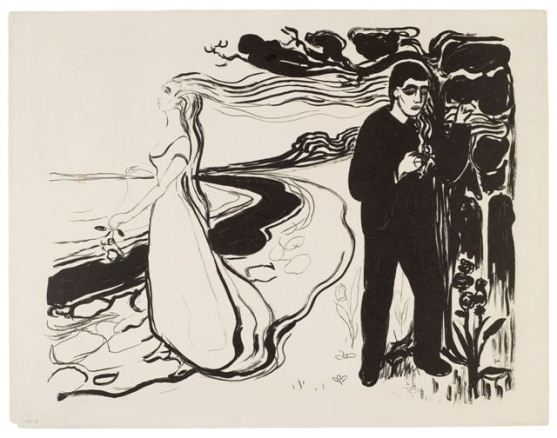

Munch had an extraordinary ability to portray deep emotions and feelings through expressive renderings of landscape. A fine example is Separation I (1896), a lithograph derived from The Frieze of Life, an important painting series. In this scene, signifying the end of a relationship, the man turns away into the darkness of the tree. The woman, bathed in light, with her back to him, looks outwards towards the water. Strands of her hair wafting above the man’s head symbolize, perhaps, his memories or ties to this lost love.

In a wall text Orit Hofshi describes aspects of Munch’s work that have special meaning for her: his ability to ‘depict locations as mediators for understanding the human condition,’ and also to exploit his materials for maximum expressive effect. Alongside Munch’s print Separation 1, Hofshi is exhibiting Trail, a large and powerful woodcut realized by the forceful linear gauging of her wood. With a nod to Munch and to early 19th century German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, Hofshi depicts a man moving through mountainous terrain, a scene that projects a true sense of solitude as well as illustrating Man’s insignificance in the face of Nature.

A wall text by Shai Zurim describes his intention to bring a breath of fresh Israeli air into Munch’s world of ‘northern depression … poignancy and melancholy.” In places of one of Munch’s sensitive portraits of himself or his artistic friends, Zurim chooses to make a drawing of a one-time local hero of Tel Aviv’s Hatikva neighborhood, the footballer Ehud Ben Tovim.

On the wall opposite to Zurim’s ink and brush drawings, is Jealousy, a Munch print depicting a love triangle between the artists and two friends, rivals for the love of the same woman. In Zurim’s version, the contorted face of Staczu Prybyszewski, a Polish poet and novelist set in the foreground by Munch, has been replaced by a self-portrait of the Israeli Zurim staring belligerently out the viewer,

Munch, for all his technical expertise and drama-filled scenes can be heavy going. The inclusion of these three contemporary Israeli artists in this exhibition, curated by Irith Hadar, definitely lightened up this viewing experience.

Prints and Drawing Gallery, Herta and Paul Amir Building, Tel Aviv Museum, closing date: November 10, 2012.