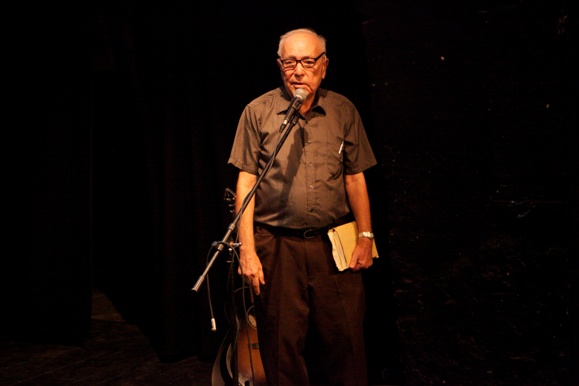

In 1965, the poet Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008) recited his poem “Identity Card” before a large gathering in Nazareth. The opening lines, “Write down! I am an Arab”, are echoed in Marwan Makhoul’s poem “An Arab at Ben Gurion Airport”. On Saturday evening, these words were recited again at the Arab-Hebrew Theater in Jaffa, where a diverse and enthusiastic audience gathered to celebrate the new translation of Makhoul’s book, Land of the Sad Passiflora (published by Keshev). “An Arab at Ben Gurion Airport” was recited in Hebrew by the editor, Almog Behar, and then in Arabic by the poet himself. His voice reverberating under the vaulted ceiling of the theater, Makhoul read his words with elegance and power, and an almost spiritual atmosphere permeated the room as audience members followed the Hebrew translation in their books.

The event was attended by some of the most distinguished and influential figures in Israel’s artistic community. Musician Mira Awad sang “I, Yosef”, a setting of another poem by Mahmoud Darwish, and dedicated her song “Bahlawan” (“Acrobat”) to Makhoul. She described working with Makhoul on the music for his 2009 play, Not Noah’s Ark. The play’s director, Norman Issa, hosted the poetry event, and his humor instantly put the audience at ease.

Ronny Somekh, one of Israel’s leading poets, praised Makhoul’s poetic style. “Marwan leads us off the highway and turns the lane into a metaphor,” he illustrated. Makhoul’s poetry paints a wide spectrum of themes – from love poems, through descriptions of the land, to character portraits, said Professor Rafi Weichert, chief editor and founder of Keshev Poetry Publications. He explained that character portraits are especially hard to write: “You need bravery to describe people.”

Makhoul spoke of his roots and the works that influenced him and his writing, such as the poems of Mahmoud Darwish and Ghassan Kanafani’s Land of Sad Oranges. He expressed his gratitude to Helicon, the Society for the Advancement of Poetry in Israel, for being the first to welcome him into the Israeli writing community. Israel Prize laureate Professor Sasson Somekh described the early days of the Hebrew-Arabic poetic collaboration, and Makhoul’s work with Helicon.

The translation of the book was a collaborative effort, said editor Almog Behar, discussing Makhoul’s experience of hearing his poems read in Hebrew. This discussion was followed by a question-and-answer session with a very active audience, and a passionate discussion of poetry and politics ensued. “If I could,” Makhoul said, “I would erase all borders. They are cuts and scratches scraped across the earth.”

An Arab at Ben Gurion Airport

I’m an Arab!

I shouted, at the doorway to departures,

short-cutting the woman soldier’s path to me.

I went up to her and said: Interrogate me! But

quickly, if you don’t mind. I don’t want to miss

departure time.

She said: Where are you from?

Descended from Ghassassanian kings of Golan is my heroism, I said.

My neighbour was Rehab the harlot of Jericho

who gave Joshua the wink on his way to the West Bank

the day he occupied the land that occupied history after him

from the very first page.

My answers are as stony as Hebron granite:

I was born in the time of the Moabites who came down before you

to this submissive ancient land.

My father a Canaanite

my mother a Phoenician, from South Lebanon of old.

My mother, her mother died two months ago

and she was unable to see her mother off two months ago.

I wept in her arms so that on-looking from Buqaya might console

the worst blow of tragedy and fate:

Lebanon, you see impossible sister,

and my mother’s mother alone

to the north!

She asked me: Who packed your bag for you?

I said: Osama Ibn Laden! But hold on,

take it easy. It’s no more than a joke in poor taste,

a quip that the realists here like me use professionally

for the struggle.

Sixty years I’ve fought with words about peace.

I don’t attack any settlement

and I don’t have a tank like you do

ridden by a soldier to tickle Gaza.

Dropping a bomb from an Apache isn’t on my CV

not because I lack qualifications,

no, but because I see on the horizon a ripple echoing

enough to the out-of-place revolt of the non-violent

and to good behaviour.

Did anyone give you something on the way here? she asked.

I said: An exile from Nayrab refugee camp

gave me memories

and the key to a house from the fabled past.

The rust on the key made me edgy, but I’m

like stainless steel, I compose self with self should I grow nostalgic,

for the groans of refugees

spread wings of longing across borders.

No guard can stop it, nor thousands

and not you for sure.

She said: Do you have any sharp implements in your possession?

I said: My passion

my skin, my olive complexion

my being born here in innocence, but for fate.

Pess-optimistic I was in the seventies

but I’m optimistic about the roars of disobedience

right now being raised to you in Gilboa gaol.

I’m straight out of the

tragic novels of history, the end of the story

a funeral for the past and a wedding

in the not far-off hall of hope.

A raisin from the Jordan Valley raised me

and taught me to speak.

I have a child whose due date I postponed, so he’ll arrive

to a morning not made of straw like today, daughter of Ukraine.

The muezzin’s chanting moves me, even though I’m an atheist.

I shout to mute the mournful wailing of the flutes,

to turn pistols into the undying strains of violins.

The soldier took me to search my things

ordering me to open my bag.

I do what she wants!

And from the depths of the bag ooze my heart and my song,

the meaning of it all slips out eloquently and crudely, within it all that is me.

She asked me: And what’s this?

I said: The sura of the Night Journey ascending the ladder of my veins, the Tafsir of Jalalayn,

the poetry of Abu Tayyeb al-Mutannabi and my sister Maram,

as a photograph and real at the same time,

a silk shawl to enwrap and protect me from the chill exile of relatives,

tobacco from a kiosk in Arraba that made my head spin until doubts got stoned.

Inside me a fierce loyalty, the wild thyme of my country,

the fieriness of pomegranate blossoms, Galilean and sparkling.

Inside me agate, camphor-wood, incense and my being alive,

the pearl that is Haifa: scintillating, everlasting, illuminating,

preposterous, relaxing in the pocket of our return for one reason

only: we worshipped our good intentions and bound

the nakba to a slip in the past and in me!

The soldier hands me over to a policeman

who pats me down and shouts in surprise:

What’s this!?

The manhood of my nation, I say

and my progeny, the fold of my family and two dove’s eggs

to hatch, male and female, from me and for me.

He searches me

for anything that could pose a threat

but this stranger is blind

forgetting the more destructive and important bombs within:

my spirit, my defiance, the swoop of the hawk in my breath and my body

my birthmark and my valour. That is me

whole and complete in a way this fool

will never see.

Now, after two hours of psychological grappling

I lick my wounds for a sufficient five minutes

then embark on the plane that has taken off. Not to leave

and not to return

but to see the soldier below me

the policeman in the national anthem of my shoes below me

and below me a big lie of tin-can history

like Ben Gurion become as always, as always, as always

below me.

Great piece, super interesting! I know a lot of non-Israelis who would appreciate a poem about being a fioreigner at Ben Gurion Airport. Has he been translated into English?

Comments are closed.